Community Voices: Disability Is Not a Disappearing Act

By Chase the Entertainer | Friday, September 12, 2025

Chase the Entertainer

“My name is Chase the Entertainer. I’m a mentally ill, physically disabled, Native American, professional magician, and I only look like one of those things.”

This is how I open every show.

It gets a laugh, which is good, because I need that laugh. Not just because it loosens the room, but because it gives me control of the story. Before they can wonder why my hands are shaking or why I needed to sit down before the curtain rose, I’ve already handed them the answer, gift-wrapped in a punchline. I’m not hiding anything. I’m not trying to make my disability disappear. I’m painting it red.

I tour the country with a one-man magic show about being a sleight-of-hand magician whose hands shake. For the record, they shake because I have something called essential tremor (ET), a neurological condition that causes involuntary, rhythmic shaking. And I get tired fast because of a condition called congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS). It’s a neuromuscular disease that basically means I have the stamina of a phone battery left in the sun.

I started using a wheelchair in elementary school, always explaining that I got really, really tired really, really fast due to my CMS. Extreme fatigue essentially. And my recovery time from over-exertion was (and is) awful. Using the wheelchair let me participate in life a bit more without paying for it for two to three days (sometimes more). At that point, people could see something was “wrong” and would give me a little extra room to be winded after walking ten feet. The chair was visible, undeniable. It was my red paint, even if I didn’t know it at the time.

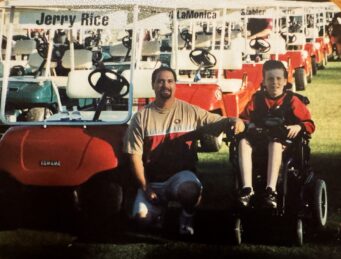

A young Chase with his father at a golf event.

When I got a little older, I learned more about how my body works and that there is no shame in sitting down. I chose to stop using the wheelchair after high school. Now, I try to pace myself and take breaks when I need to. Sometimes I overdo it, and my recovery time is still terrible. I try to manage my abilities each day and incorporate rest. But a strange thing happened when there was no longer a wheelchair to notify others that I had a disability. The symptoms certainly didn’t go away. They just got harder to explain.

Suddenly, being exhausted from one flight of stairs looked suspicious. Shaky hands looked like nerves. Or worse: intoxication. I found myself constantly trying to prove I was not lazy, not drunk, not anxious, just, you know, disabled. I was defensive. Angry. Exhausted in ways that had nothing to do with stairs.

Then I heard the late, great British comedy magician Paul Daniels say, “If you can’t hide it, paint it red.”

He wasn’t talking about a sleight-of-hand or a secret move, he was talking about a piece of stage dressing that didn’t quite meet his standards. So, instead of trying to disguise it, he made a joke about it. He leaned in. He gave it flair. And in doing so, he made it work.

It was a throwaway line, but it stuck with me.

I took the advice literally. As a street performer in San Francisco, I started calling out my tremors. Not in a sad, self-serious way – but in a joke. Something like, “In case you’re wondering why my hands are shaking, it’s not nerves. I’ve got essential tremor. And it’s essential I have it, because otherwise this trick would be way too easy.”

Chase performing a magic show in San Francisco, CA.

And the crowd… shifted. They weren’t looking for a reason to doubt me anymore. They were rooting for me. I could drop a prop and get a laugh instead of a wince. My worst fear, that they were assuming the worst about me, got replaced by something better: they got it.

Owning the thing that made me insecure took the sting out of it. It gave me freedom to focus on the show, to play, to fail, to perform. It didn’t make my symptoms go away. It made them irrelevant.

And the best part? Painting it red didn’t just help with disability.

I’ve produced theatre shows where only three people showed up. That can be soul-crushing. But instead of hiding it, I leaned in. “I got my start as a street performer in San Francisco,” I told the audience, “So I assure you I’ve performed for fewer people than this.” Suddenly, it wasn’t a flop. It was a private show. A story.

That same philosophy has gotten me through technical failures, empty venues, rough crowds, and bad days. I don’t pretend they didn’t happen. I grab a brush and paint them red.

Chase performing with Malini the Mind Reading Orange.

Not everything lands as a punchline. But for the things that do, for the tremors and the fatigue and the weird little cocktail of issues that make me me, I get to decide what they mean. I get to choose the frame.

I own it. I say, “Yep, this is mine. It’s weird. It’s not going anywhere. Let’s make it work.”

I paint it red.

Not because I want to make it pretty. But because when it’s visible, when it’s claimed, it can’t be used against me. And maybe, just maybe, someone else sees it and feels like they can do the same.

So yes, I open every show by saying, “I’m a mentally ill, physically disabled, Native American, professional magician, and I only look like one of those things.”

Because it tells you what to expect: honesty, irreverence, and a guy who knows exactly what he’s working with.

If you can’t hide it, paint it red.

Next Steps and Useful Resources

- Connect with Chase and catch his magic shows here.

- Stay up-to-date on Quest content! Subscribe to Quest Magazine and Newsletter.

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.