My Father’s Journey with ALS

By Rachel Barber | Friday, May 30, 2025

Father’s Day can be a beautiful celebration — but also a tender time for many. For those whose fathers are no longer with us, this day may carry sorrow along with sweet memories. At Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA), we support the community with those feeling that loss, and offer our empathy, love, and resources. This blog is written by one of our own MDA staff members in honor of her father, Paul Coleman, who passed away from ALS, one of the diseases MDA fights through research, care, and advocacy. Her words reflect not only a deep personal loss, but the strength of a legacy built on love, resilience, and family.

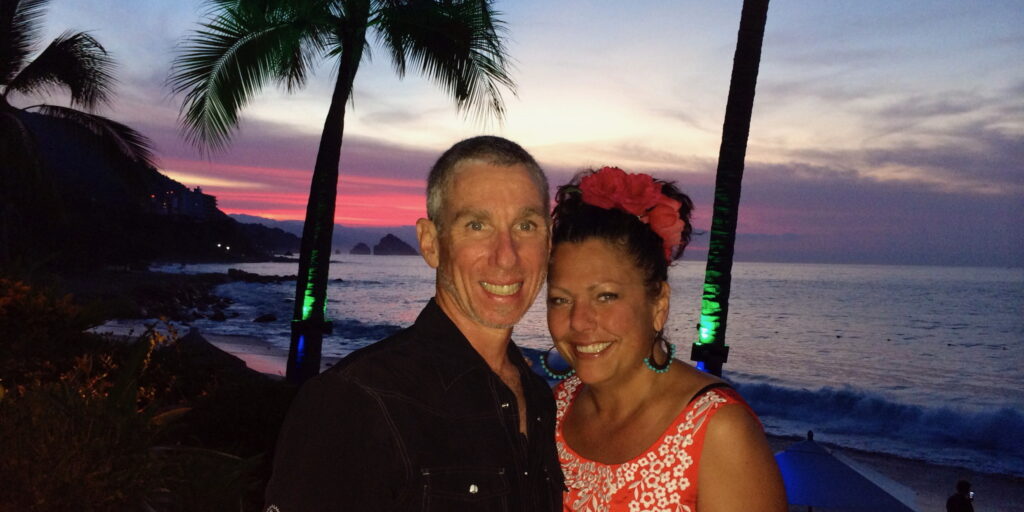

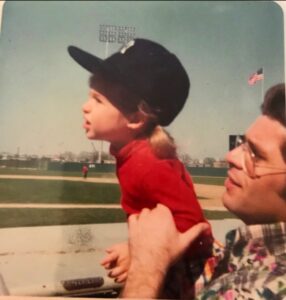

Rachel and her father, Paul Coleman

My father’s name is Paul Coleman. He was born on August 10, 1945, in the Fordham section of The Bronx in New York City. He was the third child born to Paul and Anne Coleman. Both of his parents worked hard to support their family and to provide their children with everything they needed, which is where my dad’s strong work ethic came from. I never once saw my father give up on anything. When I went through struggles and growing pains throughout my childhood, my dad would say to me “You’re a Coleman! You can do anything you set your mind to!” Even to this day, I repeat those words to myself, sometimes silently and sometimes out loud, when I find myself under pressure. Those words work. They’ve gotten me through a lot, including having to watch amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) take my dad from us.

My dad was a strong man intellectually, spiritually, and physically. When we moved to our house in New Jersey in 1976, he built a fence around the entire backyard with his own hands. There was no YouTube to reference back then, he just did it. I suspect he got some helpful tips from the guys at the hardware store or from a neighbor, but that was about it. Over the years, he also built a brick patio and two decks on our property. He loved taking care of the yard and mowing the lawn while singing at the top of his lungs. My dad was a proud patriot, a resourceful man, a good cook, and a huge New York Yankees fan who enjoyed working out regularly and loved his family deeply.

Creating a legacy of family gatherings

Spending time with his family was one of the most important things to my dad. In the mid-1980s, he came up with “Cousins’ Day”. This was a weekend of activities where all the Coleman cousins, aunts, and uncles gathered together near our house, his sister’s house on Long Island, his brother’s house in upstate NY, or a destination away from the NY/NJ area. Over the years, we went to Six Flags Great Adventure in NJ, the beach and whale watching on Long Island, camping at Bear Mountain, NY, and (my favorite trip) spent a long weekend in Newport, RI Plenty of other smaller get-togethers and trips came out of Cousins’ Day — Las Vegas, Virginia, dinners in NYC, and summer backyard or beach cookouts. My dad loved having his entire family together in one place, even if it was just for a day or two.

Rachel’s father and grandmother

My dad was also a proud man who preferred not to show weakness, which is probably why it took so long for my mom, my brother, and me to see what was happening to him physically. The guy who was physically fit and dressed handsomely slowly began to wear baggier clothes with long sleeves, even in the summer, as if to hide his appearance. We didn’t understand why, and he brushed it off if we brought it up with him. There were also moments when his mental sharpness seemed to be off.

In January 2010, we finally convinced him to see a doctor, and through my brother’s methodical research, we took him to a highly regarded neurologist for a diagnosis – all signs pointed to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The doctor observed a definite degeneration of motor nerve cells. He noted muscle wasting and weakness in my dad’s hands, chest, back, arms, and legs. My dad passed the cognitive tests but, based on what we told the doctor and what he himself observed, the doctor recognized that there were cognitive issues as well. He noted that the cognitive deficits were most likely coincidental and not necessarily tied to ALS.

His diagnosis was a punch in the gut for us. There was no treatment that could save him, no hope of him ever getting better. He was only 64 years old and should have had many more happy years ahead of him. Our only option was doing our best to manage this disease and give him the best life he could have while he was still with us. Life changed forever at that moment.

Navigating life with ALS

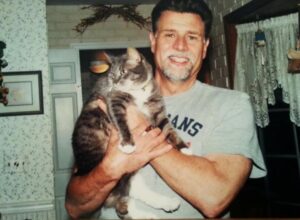

Paul Coleman

Never once did I hear my dad complain about what was happening to him. I believe that his cognitive decline – which was eventually diagnosed to be frontotemporal dementia – kept him from understanding or recognizing his reality or showing his emotions if he did comprehend the gravity of it at all. When we told him he had ALS, his reaction was very matter of fact. In my heart, I believe that the dementia was a blessing that spared him from living in a mental trap as his body withered away, knowing full well the final outcome. Having to tell the rest of the family what my dad was facing was not easy, especially having to tell his mother. How do you tell a 91-year-old mother that she’s going to outlive her child?

As a family, we were committed to making my dad’s life as pleasant, positive and normal as possible. Every weekend, I made my dad a tray of macaroni and cheese and brought it to my parents’ house for him to eat throughout the week. The high fat and calorie count helped him keep weight on. He also drank Ensure shakes to get more nutrients as eating became difficult. After three months, the doctor decided it was time for my dad to get a feeding tube because swallowing had become more difficult. Six days before Easter Sunday 2010 was the last day that my dad ate regular food. I remember being at my parents’ house for Easter and feeling awful that we were enjoying dinner together at the table while my dad sat in the other room watching TV. I asked him if he wanted me to sit with him and told him that I could eat later, but he said no thank you and that I should go enjoy my dinner. I did what he asked, but I felt so selfish doing it. The simple daily tasks that we so easily take for granted, like eating a meal, took on new weight as we watched him lose his abilities.

When my dad became more dependent on caregivers, my brother made arrangements to work remotely from my parents’ house so that he could care for my dad while my mom went to work. When my mom got home in the evening, my brother was relieved of his duties. My husband and I spent weekends with my dad so that my mom could take a break. My job became adding some comic relief to the horrible situation. I became an expert at giving my dad his meals through the feeding tube, and playing waitress with a silly accent always made him smile. Most Sundays that summer other family members came over to visit and spend time with my dad. We had a birthday party for him in August. It would be his last birthday. On November 19, 2010, at the age of 65, my dad passed away peacefully at home.

Honoring his memory with family and community

We were very fortunate that the Department of Veterans Affairs helped our family cope and manage. They guided us on unique benefits that my dad had as a veteran of the US Army. All the doctors, nurses, social workers, and staff members that were assigned to my dad’s care were a blessing and a tremendous help. The support of family, neighbors, and friends near and far gave my family comfort in every visit, email, text, phone call, and prayer.

Rachel and her father, Paul Coleman

Two months before my dad’s passing, many of my cousins and I had decided to participate in the ALS Association’s Walk to Defeat ALS in Long Island, NY. Although he was not able to join us the day of the walk, it was an opportunity to gather and celebrate my dad in a way that he would love – spending time together as a family rallying around one of our own. After he passed away, we kept that tradition for three more walks. Seeing his name on the banner for those who the walk’s participants honored was an emotional experience, but one that was worth it.

I keep my dad’s memory alive when I tell my daughters stories about the grandpa they never met. His memory is alive when I imagine how he would interact with them and love them. It’s alive at every Cousins’ Day or family event we’ve had since he left us. It’s no coincidence that I work at MDA and now am part of the mission to find treatment for ALS and other neuromuscular diseases. All the right things fell into place at the right time with the right people for me to take the role that I have, a role that allows me to honor my dad’s legacy and memory every day. Of everything we have done to keep my dad’s memory alive, the opportunity to tell his story in this blog and share it with this wonderful community is by far the most exciting, challenging, satisfying, gracious way. I know how proud he is.

Author: Rachel Barber is the manager of legal and compliance for the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) and resides in New Jersey with her husband and two daughters, ages five and eight. To keep her work/life balance in check, she loves going for longs walks at the local wooded park as often as she can – it brings her peace of mind and body. While she is there, she likes to listen to music and take photos to capture the beauty of nature.

Next Steps and Useful Resources

- Please consider a donation to help #EndALS at MDA.org/EndALS

- For more information about the signs and symptoms of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), as well an overview of diagnosis and treatment concerns, an in-depth review can be found here.

- MDA’s Resource Center provides support, guidance, and resources for patients and families. Contact the MDA Resource Center at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 or ResourceCenter@mdausa.org

- Stay up-to-date on Quest content! Subscribe to Quest Magazine and Newsletter.

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.