The Transition to Independent Living: A Parent’s Perspective

By Rebecca Hume | Thursday, July 20, 2023

Through the many chapters and changing seasons of parenthood, preparing an adult child to venture out into the world on his or her own is perhaps one of the most daunting and rewarding parenting transitions. For parents of individuals living with disabilities, that transition introduces additional considerations and emotional complexities.

Sandy Kline remembers the mixture of anxiety and excitement that she experienced when her daughter Sarah, who lives with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type 2, moved out of their family home to attend college. “It was scary. We had never had anyone else taking care of her overnight, so that was very nerve-wracking,” Sandy says. “But I was excited about her ability to express herself more and grow as an individual.”

Despite the fear that such a big change can evoke, Sandy valued that this new chapter would provide Sarah with new experiences, friendships, successes, and an increased level of autonomy and independence.

The value of independence

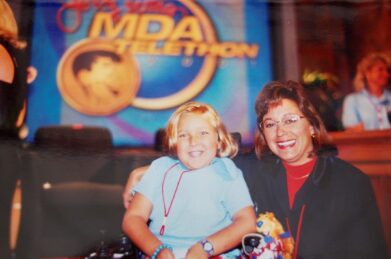

A young Sarah with her mother, Sandy.

Sarah, who is now 30 years old, was diagnosed with SMA Type 2 when she was 13 months old and began using a wheelchair when she was two years old. Growing up, Sandy provided all of Sarah’s care, with support and assistance from her own mother, Sarah’s grandmother. Sandy raised Sarah with a strong sense of independence, which was bolstered by her early experiences in Montessori preschool and her summers spent at MDA Summer Camp.

Sarah’s grandmother worked for a school designed for children with disabilities and she advised Sandy very early in her parenting journey not to treat Sarah differently because of her disability. “That is the foundation on which I raised Sarah,” Sandy says. The other foundation that she based her parenting mindset upon came from a well-timed message on a church sign. Driving home from work one day shortly after Sarah’s diagnosis, Sandy was rerouted due to construction. As she sat in traffic struggling with the new emotions and worries of having a child with a neuromuscular disease, she noticed a sign outside of a church that read: “Accept the diagnosis, not the prognosis.” Those words resonated with Sandy, motivating her to raise her child without limits.

Sandy taught Sarah the value of independence and empowered her to pursue her goals and dreams. And when the time came for Sarah to spread her wings and do just that, Sandy mitigated her fears and anxieties by reminding herself that Sarah’s independence would lead to her success and happiness.

Adjusting to changing roles

While all parents experience a wide variety of emotions and concerns when their children leave home, Sandy shares that parents of children with disabilities face some additional difficulties. “I think it is more difficult because you are having to trust not only your child, but someone else who will be providing care for them,” she says. “And you are putting a lot of responsibility on your child, who already has a lot of additional things that they must navigate. There is some guilt that you can’t be there, but you also know that they don’t want you there as they find their own way.”

No longer serving as a primary caregiver is a significant change in a parent’s role and day-to-day life. Sarah began receiving formal nursing and personal care services shortly before she moved to the dorms her freshman year of college. Having not received care from someone other than family until that time, it was a major adjustment for both Sarah and Sandy. “It was like, okay, here is this strange person that is going to be with my daughter. What if they walk out? Or don’t show up?” Sandy recalls. “The biggest adjustment was the lack of control. Which is something that all parents deal with, ours is just bigger and more involved and complicated. Before Sarah began living independently, I knew her routine and when she would need me, where she would need me, and for what reason. She was safe because I had “it” covered. She could rely on me as an extension of her physical body.”

Sandy with her adult daughter, Sarah.

While the majority of Sarah’s care is now provided by outside sources, Sandy still provides care when Sarah needs back-up or comes to visit on nights that she does not have overnight care. Close proximity allows Sarah an extra layer of security while living independently. Maintaining certain aspects of her role as a caregiver has also made the transition a little easier for Sandy.

“I think something that I learned, and am still experiencing, is that it is not a 100% cut – you don’t cut ties and stop being involved. Often, you are still very involved,” Sandy says. “In hindsight, I think the transition would have been easier for me emotionally if someone had said, ‘You know mom, she is going away to school but she is still going to need you on weekends when she doesn’t have enough coverage or on Wednesday nights when she plays power wheelchair soccer and it is too hard for someone else to do those transfers.’”

Celebrating success

Sarah chose to attend a university near home, moved to an apartment in the same town during grad school, and now lives nearby in a modified home as she pursues her doctorate. Like all parents, Sandy continues to worry about her daughter’s health, safety, happiness, finances, and a myriad of other parental concerns, but the overwhelming emotion that she experiences is pride. Amidst the balance of emotions, Sandy describes witnessing Sarah’s accomplishments over the years as an incredibly rewarding experience.

“I am proud of so much! Most definitely her ability not to let SMA define who she is,” Sandy says. “More specifically, her character and who she is as a human being. Also, her independence and ability to juggle life. Her resilience, her academic success, her career, and her ability to run a non-profit and plan a festival. How well she manages her nursing and personal care attendant staff. And her acceptance into one of the top Occupational Therapy Doctorate programs in the country!”

Advice to other parents

Sandy’s primary advice to other parents is to introduce formal care in the home as early as possible. Citing this adjustment as the most challenging aspect of transitioning to independent living, she wishes that she had incorporated formal care during Sarah’s childhood. She advises families to get help early and start small in, suggesting that they start with one day a week and work up from having an attendant provide assistance toileting to assistance showering and eventually to providing overnight care.

Talking to other parents can also make the transition easier. “Talk to friends – they are experiencing the same thing that you are, to some degree,” Sandy says. “Parents’ experience is universal.” She recalls being concerned when Sarah experienced homesickness during the first few months at school. After speaking to friends who shared that their daughters had experienced and overcame the same struggles made Sandy realize that it wasn’t just hard for Sarah, transitioning was difficult for everyone. A subtle reminder of the advice that she so frequently shared with Sarah growing up: “Quit thinking that you are different, you just do things differently.”

Sandy also shares how important it is for parents to take care of themselves, in general and especially during big transitions. She advises parents to exercise, invest in friendships and other relationships in their lives, take care of their marriages or romantic relationships, ensure that their own personal needs are not neglected – and take the time to celebrate the journey.

TAGS: Caregiving, College, Community, Parenting, Relationships, Transitions

TYPE: Blog Post

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.