10 Facts About FSHD — and a Reason to Smile

By Tana Zwart | Thursday, June 20, 2019

An older gentleman came up to me once. I had just been on TV for the Jerry Lewis MDA Labor Day Telethon talking about how facioscalpulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) affects my facial muscles and my ability to really smile and show my teeth. The gentleman put his hand on my shoulder and said with good intention, “Not everything in life is worth smiling about.”

The irony was he said it with a smile. I spent the rest of the day confused about it. I just couldn’t decide if that should be depressing, or uplifting.

Whether my happiness or amusement translates to people is a perpetual fixture in the forefront of my consciousness. So, when people aren’t reminding me of it, I am constantly reminding myself.

Whenever somebody says something funny.

Whenever a stranger walks by and smiles.

Whenever there is a camera around.

My hypersensitivity to it shows in my tendency to look down when I’m laughing, or when I say things like, “that’s funny,” or “hilarious” as an overcompensation. I may not be able to smile to the same extent as everyone else, but a sense of humor has been my primary antidote to living a life with a neuromuscular disease, and despite whether it always translates to other people, I truly have a lot to smile about.

June 20 is World FSHD Day. While FSHD is one of the most prevalent forms of muscle disease, it is still a rare disease that very few know about. Awareness is so important, both for just general understanding and empathy but also for getting proper support for cures and treatments.

Lists are one of my favorite things (because I’m kind of a square), so here’s a crash-course on FSHD in 10 facts:

- FSHD gets its name from the muscles where weakness is the most noticeable: face (facio), back (scapula), and upper arms (humeral). But the disease can also affect the lower leg and hip muscles

- FSHD affects both males and females, all races and age groups.

- Onset can range from infancy to middle age, but it usually occurs in the second decade of life. To some extent, muscle loss is just as variable.

- FSHD can be passed on by a father or a mother, and it’s almost always associated with a genetic flaw on chromosome 4 (one of everyone’s 23 chromosome pairs).

- Ten to 30% of people with FSHD have no prior family history of the disease. The cause is then a result of a genetic mutation before birth.

- Progression is relatively slow or moderate. It can take as long as 30 years for the disease to become seriously disabling. It is even possible to have FSHD but never really show signs.

- Because facial muscles are affected, it’s hard to pucker or get much strength in the mouth. Individuals with the disease have trouble with things like straws and whistling. It also affects an individual’s ability to close their eyes completely.

- Approximately 20% of people with FSHD may develop severe muscle weakness that requires a wheelchair or other mobility equipment.

- Respiratory involvement is not typical but can be seen, especially in patients with severe FSHD or those who have had the disease for decades.

- Muscle loss often occurs asymmetrically, with one side being more affected than the other.

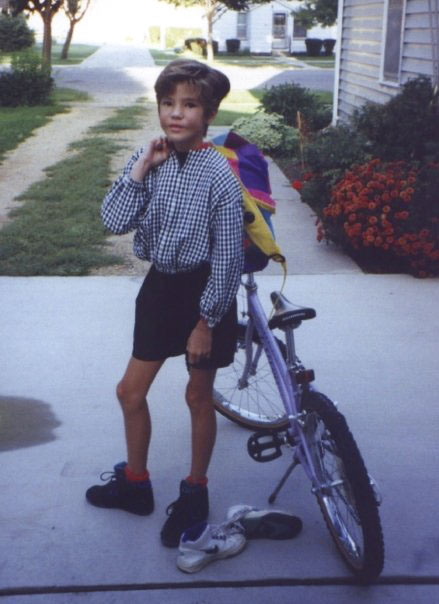

While I was finally genetically tested last May, there wasn’t genetic testing in 1992 when I was diagnosed at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. Diagnosis was made by running a lot of tests and close examination of my body. I was paraded in front of multiple doctors, told to raise my arms above my head, walk in a straight line, close my eyes, smile, show my teeth. I had needles poked into my muscles to measure muscle depth, electrodes sent through my skin to measure reflex, and surgery on my deltoid to remove a piece of muscle for a biopsy.

Today, we know a muscle biopsy doesn’t reveal anything substantial about whether muscles are affected with FSHD. I look at the faded, three-inch scar on my left shoulder and realize it is now a reminder to me of old science, and a testament to how far we have really come.

The cause of FSHD has just recently started to be understood, but I feel like holes in my story are being filled, and “whys” are being answered. I feel like we’re actually getting somewhere. All of that fundraising, all of those asks, all of that advocating…it’s paying off. Finally. And that is definitely a whole heck of a lot to smile about.

Happy World FSHD Day!

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.