4 Key Ways to Support Siblings of Kids with Neuromuscular Diseases

By Amy Bernstein | Friday, February 28, 2025

5 Second Summary

We understand that navigating life alongside a brother or sister with a neuromuscular disease can be challenging. Here, experts and families share four key ways to help siblings navigate emotions, build resilience, and feel included in the journey.

When a child is diagnosed with a neuromuscular disease, it impacts the whole family, including siblings. A child with a neuromuscular disease generally requires extra healthcare visits and special care and attention from parents. Living with a sibling with a disability often involves taking on extra responsibilities at home and cultivating awareness of accessibility and inclusion outside the home.

Emily Holl is Director of the Sibling Support Project.

“First and foremost, we recognize that siblings are on this journey, too, with parents and the child who has the diagnosis,” says Emily Holl, Director of the Sibling Support Project. “It’s important to give siblings the support they need to navigate the journey.”

Here, three families share their experiences, and Emily shares tips on helping siblings cope with emotions and build resilience.

Open, age-appropriate communication

Kaitlyn was 5 when her little brother Danny was born. Doctors noticed some issues soon after his birth, and Danny was in the NICU for about seven weeks while doctors gave him nutrients and tried to determine the cause of his difficulty sucking and swallowing. Danny came home with a feeding tube, and a few months later, a genetic test revealed Danny’s diagnosis: Bethlem myopathy. Kaitlyn began learning about the disease along with her parents, Monica Ramos and Keith Schmitz, of San Antonio, Texas.

Siblings Danny and Kaitlyn

“We explained things to her in a very open manner,” Monica says. Even before they knew the diagnosis, they tried to give Kaitlyn the information they had in terms she could understand. “Danny didn’t cry much because he was so tired, and it was hard for him to even move the muscles in his face to smile. Kaitlyn didn’t know what to make of that until we explained, ‘There’s something inside him that’s not working. We don’t know what it is, but we’re trying to find out.’”

Once they had a diagnosis and sought specialized neuromuscular care for Danny, they brought Kaitlyn to doctor’s appointments so she could hear what the doctors had to say. “We had a wonderful developmental pediatrician and nurse practitioner. As they were explaining things to us, they also explained to her, and they would tell her, ‘You can help him by holding him this way’ — just little things to make her part of the process,” Monica says.

Jessica and Ryan Hubbard, of Knoxville, Tennessee, parents to Emily and Deacon, who lives with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), also handled their daughter’s curiosity by providing as much age-appropriate information as possible. When Deacon was diagnosed as a toddler, Emily was 7, and they explained that Deacon couldn’t run fast or climb stairs because he has “special muscles.” A few years later, Deacon received a new gene therapy, and Emily started asking more in-depth questions. Jessica sat at the computer with Emily and helped her conduct research on DMD and gene therapy, guiding her daughter to websites and videos that she had vetted beforehand.

Before starting the research session, Jessica asked Emily about her specific concerns. Emily was worried that the therapy would hurt her brother. “We did read about a couple of clinical trials that had some adverse effects, and I did that on purpose so she could see how many boys went through the therapy and that only a few had problems with it, and it wasn’t terrible, and they were still OK,” Jessica says. “I wanted to help ease her worries, but I didn’t want to promise everything would be perfect because that’s not accurate.”

Expert advice: Siblings need real information about a diagnosis

Siblings Emily and Deacon

“We know from research that siblings have many of the same questions and concerns as parents,” says Emily of the Sibling Support Project. “Siblings need the same kind of information as parents, but in age-appropriate language.”

Emily recommends asking your neuromuscular care team for help explaining information on neuromuscular disease and therapies at your child’s level.

Sometimes, parents don’t share information about a disease with siblings because they don’t want to worry or confuse their child. “The reality is that a neuromuscular disease happens not just to one person but to everyone in the family,” Emily says. “By not talking with siblings, parents may inadvertently send the message that this is something we don’t talk about, and it’s not OK to ask questions.”

She cautions that when kids don’t have accurate information, they tend to put the pieces together themselves. Children — especially young children — may come to conclusions that don’t make sense, leading to fear or guilt.

Of course, parents don’t know all the answers, and it’s OK to say that. “It’s very powerful for a parent to say to a child, ‘We don’t know that right now, but we’re going to do everything we can to work with the doctors to find out,’” Emily says. “Honesty goes such a long way with children.”

Many paths to inclusion

When Danny was a baby, Kaitlyn always wanted to be there during his physical, speech, and feeding therapy sessions. “The therapists would allow her to participate, which helped her understand that this is not a little kid taking all of mom and dad’s time because they love him more; he needs that help,” Monica says.

Danny was also included in Kaitlyn’s activities. “We would take him and his feeding pump and IV poles to her Little League games,” Monica says. “It was not easy, but that made them feel connected.”

Now, 13-year-old Kaitlyn is a competitive gymnast, and the whole family travels around Texas and the country for her competitions. “Danny has a special shirt that he wears for her meets, and he’s right there yelling and screaming when he sees Kaitlyn,” Monica says.

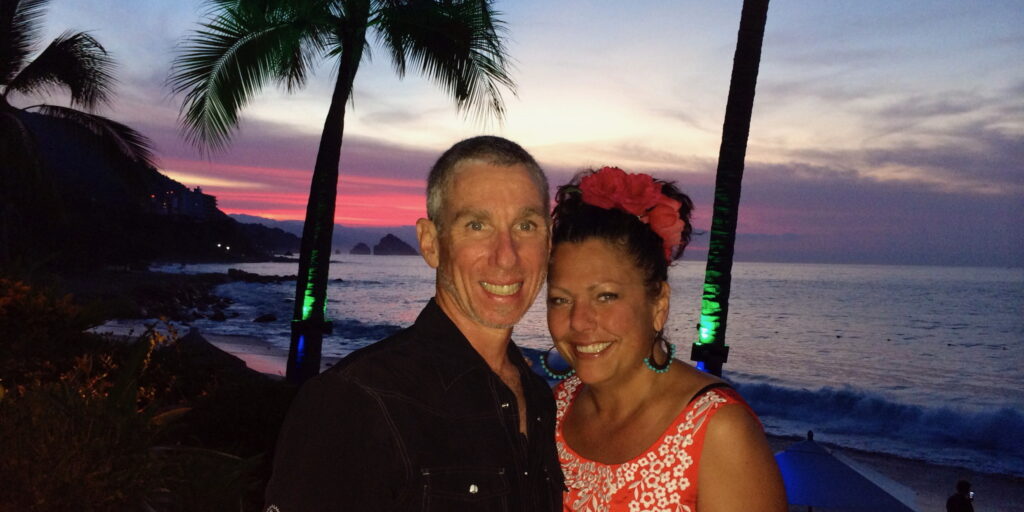

Siblings Kara and Emmaline, with parents, Jason and Amy

Inclusion also means encouraging typical sibling relationships and friendships. Kara, 15, and Emmaline, 11, who lives with collagen VI-related dystrophy, have their own groups of friends. Their parents, Amy and Jason Johnson, of Nashville, Tennessee, have always encouraged each of them to include the other when playing with friends.

Recently, Kara wanted to go to the mall with a friend, and Jason offered to give them a ride if Emmaline went with them. “They all three had a good time. Emmaline was strolling around in her electric wheelchair with the two older girls, and they were shopping together,” he says.

Expert advice: Get siblings involved in important conversations and activities

According to Emily of the Sibling Support Project, siblings need to be included in conversations about the diagnosis and treatment plan. This allows them to ask questions and better understand their brother’s or sister’s needs.

A sibling may take an active interest in their brother’s or sister’s care, but their role may change over time as they get involved in their own activities. This is natural, and they should be encouraged to pursue their interests.

Sometimes, siblings feel guilty for doing things their brother or sister can’t. “We present ability as being on a spectrum; we all have things we are good at and things we need help with, and we try to normalize that,” Emily says. “We could say to a sibling, ‘You might learn to ride a bike first, and maybe your older brother will not be able to ride a bike, but there are things he can do really well.’”

It’s also important to look at each child as an individual and consider their unique needs. How you support each child and how they support each other may look different based on what works for your family.

Handling big emotions

According to her mom, Jessica, Emily has always been a worrier, but her anxiety got worse after her brother was diagnosed with DMD. “At that point, she started seeing a counselor,” Jessica says. “I’m sure there are things she doesn’t want to tell me because she doesn’t want to worry me. Having someone else to talk through that with has been really beneficial for her.”

Sharing parents’ attention is a natural source of conflict between siblings. When a sibling with a neuromuscular disease needs extra care, those feelings can be heightened.

When Kaitlyn started middle school, Monica saw this issue come to a head. “She started getting very moody, and we tried to ask her, ‘What’s going on?’”

Kaitlyn told her parents that she felt like she couldn’t talk to them because they were so busy with Danny. Monica and Keith immediately started setting aside time to spend with her one-on-one. “There would be time for just the two of us to talk and connect, whether I was taking her out for pizza or spending time with her at her gymnastics practice,” Monica says. “And there were times when she and her dad would go to breakfast together.”

Amy also takes opportunities to give Kara one-on-one time. Emmaline has a long bedtime routine, which involves Amy stretching her legs and setting up her breathing machine. “I’m in Emmaline’s bedroom for a while, so when I go to Kara’s room to say good night, she wants me to sit down and talk,” Amy says. “It’s the end of my day, and I’m tired, but I know it’s important, so I’ll sit down and listen to whatever she wants to bring up. Taking that time to sit and talk with her is always worth it.”

Amy acknowledges that Emmaline’s medical care can take a lot of time. One way she addresses that is by scheduling Kara’s healthcare appointments separately from her sister’s, even if it is less convenient. “I want Kara to know that she has every right and should take care of herself,” she says. “Her health is just as important as Emmaline’s.”

Expert advice: Help siblings talk about their feelings and know it’s OK to not be OK

Having a sibling with a neuromuscular disease can bring up big feelings, and sometimes, kids need help coping with them.

“I think therapy can be a great tool for siblings,” says Emily of the Sibling Support Project. It may be appropriate if you notice a change in their behavior or if they are acting out to get attention. But even if a sibling is not exhibiting these behaviors, it’s important to check in with them. “Sometimes a sibling is a classic overachiever — they’re getting good grades, they’re participating in activities, they have friends. But they may be putting pressure on themselves to be the perfect kid so as not to put more burden on their parents. We want to encourage their achievements, and we also want to let them know that it’s OK to not be OK all the time.”

Setting aside special time with siblings is a great way to give them the attention they need and do those check-ins.

“The reassuring message for parents is that a little time can go a long way with siblings,” Emily says. “It might be something as simple as bringing a sibling on a trip to the grocery store and finding ways to make it fun — play a game in the store or stop for a treat afterward. It might be letting the sibling stay up 20 minutes after you put your other child to bed and doing a puzzle or reading together. Siblings will appreciate those small, consistent gestures.”

Planning for the future

While children typically live in the moment, having a sibling with a neuromuscular disease may lead them to think ahead early. Jessica was surprised when Emily seemed concerned about her brother’s future in third or fourth grade.

“She started asking questions, like, ‘What will happen to him? Will he always be in a wheelchair?’” Jessica and Ryan addressed Emily’s questions with help from Deacon’s doctors and told her when they didn’t know the answer. Emily is 11 now. “At this point, she is fully aware of Deacon’s DMD, and she knows what the future could look like,” Jessica says.

Monica and Keith know that Danny’s future also affects Kaitlyn, who is close to her brother. The family jokes that Kaitlyn will take Danny to college with her because they don’t want to be separated. In fact, Monica and Keith want her to have the opportunity to go to college and experience young adulthood without being a caregiver.

“We have paperwork set up for Danny, should anything happen to my husband and me before he comes of age or if he’s not able to support himself,” she says. “We want Kaitlyn to be able to have her own life and do what she needs to do for herself.”

Expert advice: Start long-term care discussions early

“Even young siblings are thinking about the future care of their brothers and sisters,” says Emily of the Sibling Support Project. “They tend to realize early that they are likely the next generation of caregivers.”

Emily recommends beginning to think about the future early and involving siblings in those discussions. Transition points are natural times to start these conversations, such as asking a sibling for their input before an IEP meeting or at the beginning of the school year.

It can be difficult to talk about the long-term future, but discussing the unknowns and challenges, as well as each family member’s priorities and hopes, helps a family be ready for whatever may happen.

“The reality is that most siblings will step into the role of caregiver at some point,” Emily says. “If we have a voice and choices along the way, we come to that role with much more willingness and capacity because we can prepare for it.”

In Their Words

What advice would you give other parents?

“We always want to pay more attention to the one that we believe needs us most because they have a neuromuscular condition. But the reality is that a lot of times, they’re not as dependent on us as we think they might be. It’s important to let go a bit and see what happens. Not only does that help the child, but that helps you as a parent and as a spouse, and it helps your other child.” —Monica Ramos

“Siblings need support for their mental well-being. They may not verbalize what they’re feeling, they may be internalizing a lot, so it’s even more important as they’re developing to take care of their mental health and make sure they have an outlet to speak about it.” —Jessica Hubbard

“I think taking care of ourselves and our kids seeing their parents do that is important. We try to exercise, and we go out on dates or run errands together. For all kids, but especially siblings, it’s important to know they should take care of themselves, too.” —Amy Johnson

“Find ways to incorporate everybody and make sure everybody feels comfortable and gets to do things they want to do. It may look different when you have special challenges, but I think if you face those together as a family and talk through them, you’ll make it work.” —Jason Johnson

Next Steps and Useful Resources

- Download MDA’s Support for Siblings of Children Living with a Neuromuscular Disease information sheet.

- Watch the Sibling Support expert-led webinar.

- Listen to Siblings Tell All, a Quest Podcast episode. Listen

- Explore more Quest Media content for parents.

- Stay up to date on Quest content! Subscribe to Quest Magazine and Newsletter.

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.