Q&A: Understanding Bethlem Myopathy

By MDA Staff | Friday, November 18, 2022

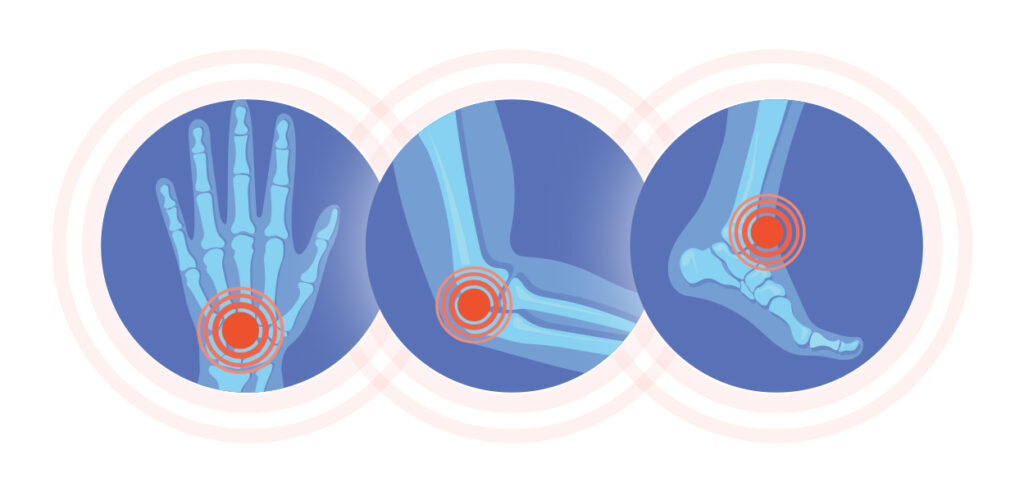

Bethlem myopathy, also called Bethlem muscular dystrophy, is a rare disease affecting skeletal muscles and connective tissue. Considered a type of congenital muscular dystrophy, it was initially recognized in the 1970s by two Dutch physicians, Jaap Bethlem and George K. van Wijngaarden, and is characterized by slowly progressing muscle weakness and joint stiffness of the fingers, wrists, elbows, and ankles.

Carsten Bönnemann, MD

The progressive weakness can eventually affect ambulation (the ability to walk and move around) and respiratory function. The severity of the weakness and stiffness can vary greatly, however. In addition, some may experience joint pain, which is thought to involve the joint connective tissue and cartilage, but this has not been studied extensively.

Symptoms of Bethlem myopathy can begin in any age group and can even be noticed before birth through decreased fetal movement. It is estimated that fewer than 5,000 people in the United States live with the condition.

To learn more about Bethlem myopathy, we spoke with Carsten Bönnemann, MD, senior investigator and chief of the Neuromuscular and Neurogenetic Disorders of Childhood Section at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

What is Bethlem myopathy?

It is a degenerative muscle disease caused by mutations in one of the three genes, COL6A1, COL6A2, and COL6A3, that specify the genetic code for a protein called collagen type VI. Collagen VI is an important component of the extracellular muscle matrix (ECM) — the substance that surrounds the cells of a tissue, such as muscle, and provides physical and biochemical support. The ECM also is found in other tissues such as skin, tendons, and joints.

Although symptoms are frequently evident in early childhood, the disease course is prolonged, allowing for ambulation into adulthood.

When it runs in families, Bethlem myopathy is typically inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, which means a person has to inherit a flawed gene from only one parent to have disease symptoms.

How does it fit into the congenital muscular dystrophy category?

Mutations in the same three collagen VI genes that lead to Bethlem myopathy can also cause a more severe condition referred to as Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy (UCMD). Collagen VI-related muscular dystrophies occur within a spectrum of severity, with UCMD on the severe end and Bethlem representing the milder end, with cases of intermediate severity connecting the two ends of the spectrum.

As noted by Bethlem and Wijngaarden, Bethlem myopathy can also be clinically evident at birth or in early childhood, just with considerably milder symptoms compared to UCMD. In other individuals, it may only become evident later in life. But there are no fundamental differences in the disease’s causation; it is just the degree of severity with which it plays out.

What is the current standard of care?

The standard of care includes careful and proactive monitoring for pulmonary (lung) and orthopedic (musculoskeletal) complications, as well as physical therapy that includes moderate exercise and stretching. Sometimes surgical interventions are performed, such as lengthening the Achilles tendons, which often show the most prominent contractures.

Rare diseases can be difficult to diagnose. Are there any recent or upcoming advances that could streamline the diagnostic journey?

The characteristic combination of weakness and multiple joint stiffness results in a suggestive clinical picture that should help clinicians suspect a diagnosis of Bethlem myopathy upon physical examination. In addition, certain patterns of muscle involvement on imaging tests (such as with muscle MRI) have also been highly suggestive of the diagnosis.

But even without a specific clinical suspicion that the disease might be present, the more common use of gene panel and whole exome testing now leads to the discovery of the disease-causing mutations and, hence, a diagnosis. On the other hand, the same type of testing also frequently results in the detection of “variants of uncertain significance” in the collagen type VI genes, which must then be further evaluated by a specialist in the clinical context of the patient to avoid a misdiagnosis.

Are there any promising therapies on the horizon?

There are exciting new developments in gene-directed therapies based on the concept that inactivating a dominantly inherited mutation will result in significant improvement of disease symptoms.

In Bethlem myopathy, effective inactivation of the flawed copy of the disease-causing gene would allow the other healthy copy of the gene to produce collagen VI in an undisturbed manner, which should be enough to maintain good collagen VI matrices.

These approaches are still in the preclinical phase and are advancing toward testing in animal models. An important hurdle to overcome is effective targeting of the cells that make the ECM in muscle, because it is in these cells that collagen type VI is made. So it will still be a few years until one of these therapies is ready to be tested in people, but sometimes breakthroughs can happen quickly.

Next Steps and Useful Resources

- Browse our Diseases A-Z library of disease-specific content.

- Learn more about how genetic neuromuscular diseases are inherited.

- Read more of our Spotlight series on rare diseases.

TAGS: Clinical Trials, Drug Development, Gene Therapy, Research, Research Advances, Spotlight

TYPE: Featured Article

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.