![iStock-1316024196 [Converted] iStock-1316024196 [Converted]](https://mdaquest.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/FB-SMART-iStock-1316024196-e1658418268269-1024x512.jpg)

What You Should Know about the Smart Homes and Accessibility

By Shaila Wunderlich | Friday, May 13, 2022

5 Second Summary

The smart home is a reality for many individuals. While people choose to concentrate on the latest products and capabilities of the home, the most important facts are the ways users are accessing those products and channeling those capabilities in their homes. Smart homes provide accessibility for homeowners with disabilities.

You’ve probably heard of the “smart home.” For close to two decades, it has been a regularly covered topic across all sectors of media. Each year, a story in a magazine, on prime-time news, or in an industry outlook report shows a futuristic take on a home that is automated to the point that it appears to read its occupant’s mind. But what began as “the home of tomorrow” has become increasingly practical as new products and technology are rolled out on the market.

Today, the smart home is a reality. Its story, meanwhile, is less about the latest products and capabilities and more about the ways users are accessing those products and channeling those capabilities in their homes. At the forefront of this grand experiment is the population that stands to benefit from it the most: homeowners with disabilities.

At the fingertips

Every evening when Paul Robertson goes to bed, he touches a “Good night” button on his smartphone, triggering all the lights to turn off and the doors to lock in his Ocean City, Maryland, home. Automated lights and doors are not new to the disability community. What is relatively new is the ability to corral and control them (and oodles of other home functionalities) through a single, streamlined hub.

Paul Robertson uses a home-automation system to tie together his lighting, thermostat, and home security.

“My lighting is on a Lutron app. My thermostat is on a Honeywell app. My door locks are on an app called Vera,” says Paul, who lives with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD). “But rather than having to open each app separately to control their individual functions, I have them rolled under one home-automation system that accesses and controls them all.”

Paul uses a system called ELAN, but other examples include Amazon Echo, Aeotec Smart Home Hub, and Apple HomePod. Most act as both the hub for individual apps as well as the interface through which homeowners control them. Each offers their own menu of features and app-compatibilities.

The “Good night” feature Paul relies on to close out his days is a prime example of home-automation’s other new frontier: customization. Through capabilities known as “routines,” “schedules,” “environments,” or “scenes,” homeowners can orchestrate multiple functionalities around specific daily tasks and events — whether it be the start and end of each day, arrivals and departures, caregiver visits, or mealtimes. These custom settings can be launched on command (via touchscreen, voice commands, or motion-sensor triggers) or on a schedule (via timers).

Paul marvels at the time and effort he saves from not having to walk from light to light, door to door, every time he goes to bed or leaves the house. “These kinds of things aren’t a big deal to people who aren’t mobility-challenged, but they’d take me a half-hour or more,” he says.

Favorite features

As Paul attests, if there’s one smart-home feature that appears to be gaining the most traction with the disability community, it’s lighting. Before Jennifer Baker, 34, had smart lighting installed in her family’s Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, house, lights-out time was dictated by her mother, Patty. “What if I wasn’t ready for bed at 8 p.m.?” says Jennifer, who lives with Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD). Thanks to Roku and Amazon Echo dashboards on her smartphone and watch, Jennifer now controls her own lights, TV — and evenings. “It makes a big difference in my sense of independence,” she says.

Meanwhile, Patty favors the security provided by her daughter’s tech. “She’s dropped her phone several times and couldn’t get to it from her wheelchair,” Patty says. “Her nurse and I weren’t able to reach her, and we panicked.”

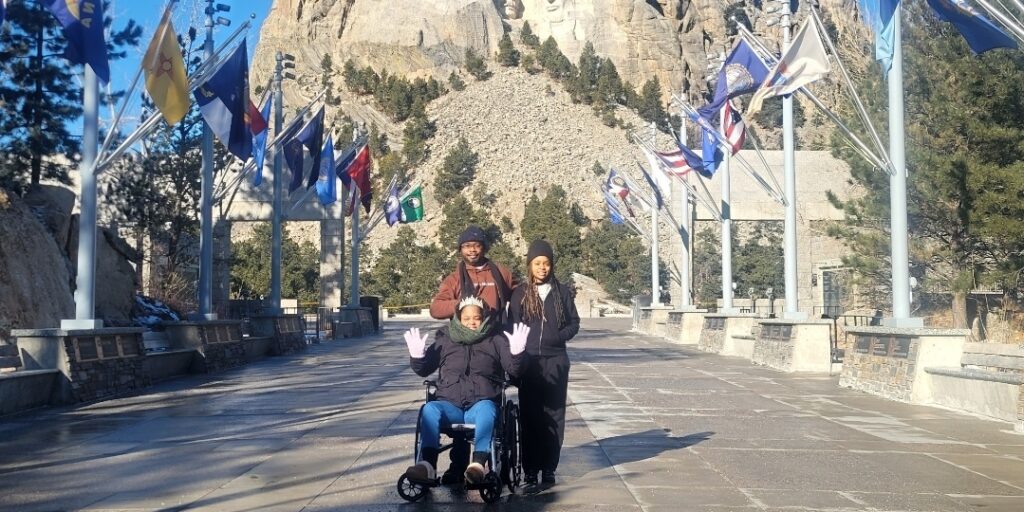

Smart-home capabilities make Jennifer Baker feel safer and more independent.

An Alexa voice-control plug-in on Jennifer’s smart watch now permits her to call for help when she drops her phone. “It definitely makes me feel easier about leaving the house,” Patty says.

As Jennifer’s disease progresses, she can add features with higher levels of automation, like Alexa Guard. Introduced in 2019, this Echo-compatible system triggers lights, alarms, and emergency calls when it detects smoke, flooding, or the sound of doors and breaking glass.

Alexa’s voice control capabilities can also be used to open and close doors in your home. In 2021, Open Sesame introduced a voice interface accessory to their line of automated door operating systems. This product allows homeowners to connect their Open Sesame door operators (both new and old models) to Wi-Fi and Alexa.

Amber Ward, OTR/L, occupational therapy coordinator at Neurosciences Institute-Neurology, Atrium Health, in Charlotte, North Carolina, notes that power wheelchairs are even beginning to get in on the act. Some of the latest models are equipped with infrared technology that can be used to control devices, like speakers, televisions, and tablets. “They act like universal remotes that you can operate with your hand, head, or lip, as long as you’re within line of sight from the device you’re trying to control,” she says.

Affordable access

“When I started in this industry, having voice control on a house’s lighting system could cost upwards of tens of thousands of dollars and take weeks or months to get,” says Matthew Colvin, rehabilitation technician for ImproveAbility, an Austin, Texas-based consulting company that provides assessments, recommendations, and installation services for people seeking assistive technology for their homes. “Now, it’s closer to several hundred dollars, and you could find it on the shelf at the local Home Depot.”

Indeed, home-remodeling reviewer Fixr.com estimates the sum for automating an entire home is less than Matthew’s old estimate for lighting alone — around $5,500. The existence of Matthew’s company itself is another sign of changing times. With each passing day, it becomes easier to find professional help in choosing, installing, and even buying assistive technology for the home. In 2021, Lowe’s launched “Livable Home,” an initiative to provide affordable, accessible smart-home solutions as well as expertise and installation services.

The basic requirements for a fully automated home start with home products that can connect and interact with a user and other smart devices. These days, the list of options is long and includes light bulbs, switches, lamps, door openers, doorbells, cameras, speakers, thermostats, faucets, washers/dryers, and refrigerators. In fact, a smart plug can turn a simple device that plugs into the wall — such as a space heater, humidifier, or Christmas tree lights — into a connected device that you can control from your phone.

The next requirement is a system and interface (ELAN, Amazon Echo, Apple HomePod, etc.) that allows you to corral and control those smart products. Interfaces may be controlled by touchscreen, voice commands, or motion sensor triggers, according to a homeowner’s preference and abilities.

While outfitting an entire home at once (as Paul did) is certainly convenient, Matthew recommends homeowners get their feet wet with one or two features at first. “Do it a step at a time, get comfortable, figure out what works,” he says.

As Matthew gets to know his customers and their conditions, he can prepare their homes for future capabilities. “We may start with a tablet you operate with your hand, but when they get to the point where they can no longer touch it, I could already have the hardware installed that allows eye control,” he says. “All they have to do is call me and I’ll launch it for them.”

And that proves the home of tomorrow truly is a reality today.

Shaila Wunderlich is a St. Louis-based writer with more than 20 years’ experience in the publishing industry.

Smart Spending

Depending on the specific products you choose and the method of installation (DIY or professional), costs for the average smart-home setup range from $1,500 to $7,000. Financial assistance options exist, but they require a fair amount of research and must be vetted before you make any purchases. Begin with the resources here, in the order listed.

- Private insurance and Medicaid. Most private insurance does not cover assistive technology, but check your specific plan to be sure. Medicaid offers some waiver or voucher options that vary by state, and both Medicaid and private insurance require prescriptions or medically authorized documentation of necessity. Look to your MDA care team for help collecting and submitting that paperwork.

- Federal- and state-funded assistance. “Every state has state or federally funded assistive technology programs that may offer anything from loaner equipment to help with installation,” says Amber Ward, OTR/L, occupational therapy coordinator at Neurosciences Institute-Neurology, Atrium Health, in Charlotte, North Carolina. Visit the Association of Assistive Technology Act Programs to find the programs in your state.

- Local vocational and service organizations. These include grants from state-based independent living/vocational rehabilitation organizations and scholarships from local service clubs, such as Elks and Lyons. Check your local chapters for specific opportunities.

- Private charities and causes. “These are often local and diagnosis-specific,” says Amber, who points to the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) group Team Joseph as a prime example. Social media groups formed around your neuromuscular disease can be a great place to identify similar resources.

Next Steps and Useful Resources

- Visit the Association of Assistive Technology Act Programs to find the programs in your state.

- Browse you state’s Medicaid page for possible waiver or voucher options for assistive technology.

- MDA’s Resource Center provides support, guidance, and resources for patients and families, and other services. Contact the MDA Resource Center at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 or ResourceCenter@mdausa.org

- Stay up-to-date on Quest content! Subscribe to Quest Magazine and Newsletter.

TAGS: Featured Content, Innovation, Resources

TYPE: Featured Article

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.