CMT and Your Feet: Surgery Sometimes, Bracing Often, Caution Always

By Updated by Joanna Buoniconti | Monday, February 12, 2024

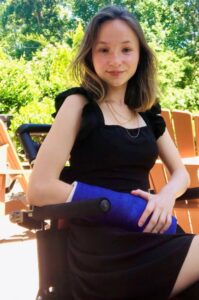

Lily S., 16, of South Carolina, remembers what it was like to play and be active as a child.

“I was able to participate in gymnastics after having extensive surgery.”

Lily S. has had surgeries on her feet and hands to improve their function.

When she was 4 years old, Lily was diagnosed with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) type 1E and hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP), which are both caused by genetic mutations in the peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22) gene.

Her first surgery was a bilateral foot reconstruction because she had extreme club foot and could no longer walk. Since then, she has had calcifications caused by trauma from surgery removed from her left heel. Lily has also had tendon transfers on her hands and wrists to improve their function.

CMT’s progression is notoriously difficult to track and predict, with each person’s symptoms varying, and Lily’s case progressed quickly. She now lives with chronic pain but is determined to focus on the function she has and to keep going. She uses shoe inserts with carbon fiber ankle-foot orthoses (AFOs) to help her stability while walking and a wheelchair on days when she’s fatigued.

“My braces feel like a missing piece to my body, as they provide me with so much mobility,” Lily says. “I feel lighter and more agile as soon as I put them on. I am so grateful for my amazing, relentless orthotist who works tirelessly to ensure my comfort. Braces are the single best thing I have done for my health and quality of life.”

What is CMT?

CMT was originally named for three doctors who first described it. In 1886, Jean-Martin Charcot and Pierre Marie in France and Howard Henry Tooth in England identified what they thought, erroneously, was a spinal cord disease.

We now know that CMT is a genetic disease of the peripheral nerve fibers, long “wires” that bundle together to form cablelike structures, or nerves, that run between the spinal cord and the periphery (outside edges) of the body. The motor nerves carry signals that cause muscles to move, and the sensory nerves send signals back to the spinal cord that convey pain, temperature, vibration, and other sensations.

CMT affects some 30 people per 100,000. Since the early 1990s, scientists have identified more than 20 genes that, when flawed, can cause CMT. Some of these genes affect the nerve fibers, while others are needed to form and maintain myelin, the insulating coating around each fiber.

Either way, the symptoms are similar: mild to severe weakness, especially in the hands and feet, often accompanied by mild to moderate loss of sensation and less often by burning or tingling pain in those areas, beginning in childhood or adolescence.

How CMT affects feet

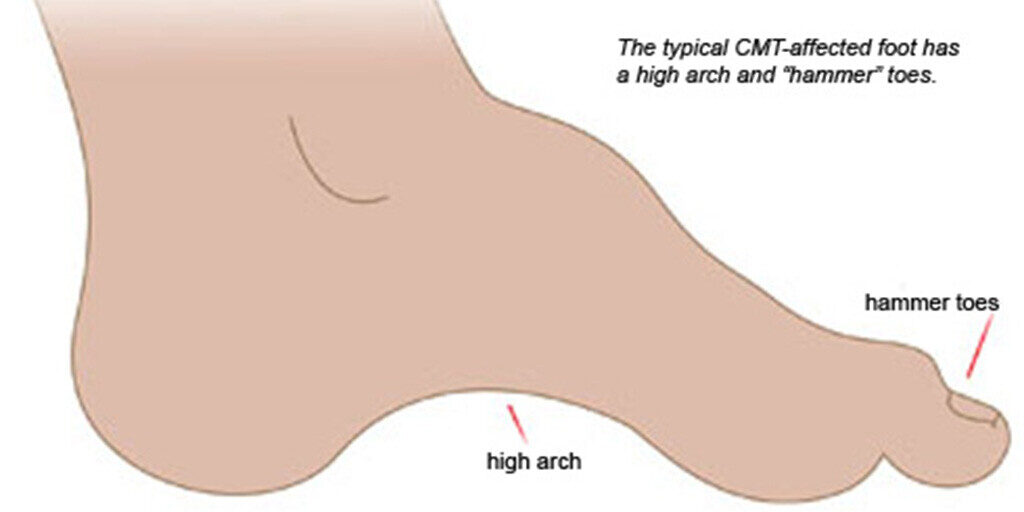

“The typical problems with feet are the shape of the arches and the difficulties with the joints that walking with abnormally shaped feet causes,” says neurologist

Michael Shy, MD, an MDA research grantee at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, where he co-directs the MDA Care Center and directs a CMT clinic. “Not every single person who has CMT has high arches. Some people have flat feet. But many patients have abnormal feet.”

Another common problem is hammer toes, so named because the toes are curved into a shape resembling the hammers that piano keys activate.

Dr. Michael Shy

“Generally, we start with shoe inserts and AFOs” to align the foot, Dr. Shy says. “In my opinion, when foot deformity is so severe that patients walk on the sides of their feet, when the Achilles tendons are very tight, or when a high arch is extreme, it’s worth considering surgery. Also, when hammer toes are so severe that patients are developing calluses or blisters on the tops of their toes, many would consider surgery to straighten the toes.”

Carolyn Black, MD, a neuromuscular and electrodiagnostic medicine physician specializing in bracing at Providence St. Luke’s Rehabilitation Medical Center in Spokane, Washington, recommends that anyone who has CMT should try to understand their options and have an in-depth conversation with a doctor who is familiar with hereditary neuropathy.

“Having access to an MDA or CMT-specific multidisciplinary clinic is hugely beneficial,” Dr. Black says. “It allows for better conversations to happen with input from people with different expertise and management styles, including physiatrists, neurologists, orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, and orthotists.”

Shoe inserts (orthotics)

“Most people with CMT will benefit from some type of orthosis at some point in their life,” Dr. Black says. “The type of orthosis an individual might need depends on the biomechanics of the ankle joints.” (Orthotics and orthoses are both supportive devices, but the first term is often used to mean a shoe insert and the second to mean other kinds of appliances, such as AFOs.)

People with CMT also need good walking or athletic shoes with removable insoles to make room for the orthosis. Dr. Black likes Nike and Skechers slip-on shoes that make it easier to put shoes on without using your hands. She also recommends Billy Footwear for stylish shoes that let you unzip the whole top of the shoe to get orthotics and AFOs in and out easily. If you prefer other shoes, use a long-handled shoehorn to put them on.

The key to foot orthotics, she says, is “to get the ankle and hindfoot in as close to neutral, or normal, alignment as we possibly can.” Orthotists, the healthcare professionals who make and fit orthoses, often can find a way to get a foot into better alignment.

Ankle-foot orthoses (AFOs)

When orthotics aren’t enough, doctors recommend AFOs, also called braces.

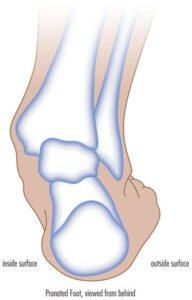

Sometimes, the muscles in the front of the shin and outside of the calf weaken sooner than the muscles that control the toes or turn the ankle inward and point it down. This imbalance changes the alignment of the ankle and makes it harder to walk.

When foot drop (difficulty lifting the front of the foot) is the main problem, an off-the-shelf AFO made of strong, light carbon fiber works well. These help a person lift their toes off the ground and avoid tripping while walking.

“Carbon-fiber options are lighter weight, more flexible for active people, and can help add a ‘spring’ to your step,” Dr. Black says. “But more often than not, we see folks with CMT who have had foot changes already, and that off-the-shelf type of device doesn’t accommodate the foot changes.”

A custom-fitted, plastic AFO with a hinge at the ankle joint — for walking on uneven ground, stairs, and driving — is probably the most commonly prescribed device for CMT.

“If you have problems with pronation [the ankle leaning inward when standing] or supination [the ankle leaning outward when standing] in addition to foot drop, then a custom AFO will provide more support to the ankle joints. It can improve the ankle alignment and foot clearance simultaneously,” Dr. Black says.

Plastic AFOs are more easily custom-fitted to the exact shape needed and can be designed to provide more support or allow more flexibility. Custom AFOs run in the hundreds of dollars, but because they are categorized as medically necessary, they are usually covered by insurance. Most insurance companies will follow Medicare rules and allow for an AFO to be replaced every 5 years.

Dr. Shy cautions his patients to beware of advertisements for “miracle” braces. “None of these work for all people,” he says. “Advertising for special braces should be viewed with caution.”

Foot surgery

The recommended timing and extent of foot surgery for CMT are still being debated among surgeons and neurologists, but there are several areas of general agreement, Dr. Shy explains: “If an individual’s Achilles tendons are extremely tight, such that the patient is essentially toe-walking, then lengthening the tendons could be considered. If an ankle cannot be brought into a ‘neutral’ position by a brace such that the foot strikes the floor evenly, then reconstructive surgery, including tendon transplants, are usually considered,” he says.

Other considerations for pursuing surgery include the position of the arches and toes: “If the heel moves in so that it changes the angle of the foot, this is often addressed surgically, and if the arch is extremely high, this can be reduced surgically. Straightening hammer toes can be challenging because the ‘pinning of the toes’ does not always hold, so we tend not to recommend this unless the tops of the toes are developing corns or blisters from rubbing against the top of shoes.”

Foot surgery is something people should generally hold off on until they’ve pursued well-fitted orthotics or orthoses and, if need be, physical or occupational therapy to supplement that, Dr. Shy cautions.

Phasing out fusions

“Foot surgery is common in CMT, but the types of foot surgeries performed are changing,” Dr. Shy says.

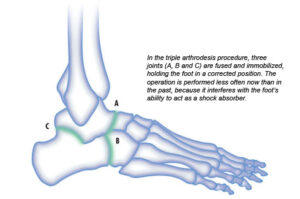

The triple arthrodesis procedure, which involves fusing bones to stabilize ankles, is done less frequently now. There’s a concern that any surgery involving bone fused to bone will cause significant arthritic problems, including pain, after several years.

Current surgical approaches typically involve osteotomy, which is cutting a bone to reshape or realign it, rather than fusion, which takes away motion and doesn’t hold up over time. (Toes, however, may need to be fused.)

Tendon transfers

Payton Rule poses with her service dog at her college graduation.

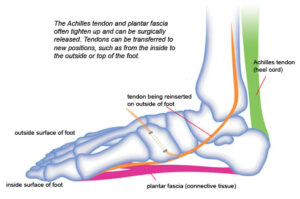

In CMT, it’s common for tendons around joints to weaken or contract. This may require surgery to release tight tendons or move tendons from stronger muscles to weaker muscles.

Another young woman with CMT, Payton Rule, 25, who currently lives in St. Louis, Missouri, had a procedure when she was 20 to lengthen the Achilles tendons on both of her feet. Before the procedure, her heel cords were so tight that her feet could not rest flat on the ground, and even with AFOs, her ankles would rotate outward to compensate for the lack of range of motion.

The procedure helped restore the range of motion in Payton’s ankles, allowing her to use her Hemi-Spiral Noodle AFOs to walk without putting extra strain on the other areas of her foot.

A band of connective tissue (fascia) that runs from the heel bone to the ball of the foot on the sole (plantar surface) often tightens up as well. A plantar fascia release loosens this connective tissue.

When foot deformity is involved, Dr. Shy sometimes recommends tendon transfers, which help use an individual’s good motor strength by moving a strong tendon to an area where there’s a deficiency.

Typically, people with CMT have a strong posterior (back) tendon on the inside of the foot. When this tendon remains strong while others weaken, it contributes to foot deformity. Surgeons may remove that tendon from the inside of the foot and move it to the outside of the ankle to work in an area where there is weakness. Tendons can also be transferred to the top of the foot to help with lifting it during walking.

About half the time after a tendon transfer, muscles (which are attached to bones via tendons) retrain themselves to work with the new tendon. The rest of the time, a transferred tendon simply acts like a piece of rope holding the foot in place. In either case, the procedure redistributes the forces on the foot and puts the foot in a better position.

Dos and don’ts of CMT-affected feet:

- Protect your feet from blisters and cuts. If you’ve lost sensation, examine your feet frequently for injuries, and don’t wear shoes or orthotics that rub. Wounds that aren’t healing need prompt attention.

- Avoid scalding yourself. If you lack sensation in your feet, test the bath water with another part of your body.

- Avoid broken bones, which can complicate matters. If you’re falling more than once a month, rethink how you’re managing your foot problems.

- Work with specialists who understand CMT, with its unique combination of weakness, loss of sensation, foot problems, and progressive course.

Dos and don’ts when considering foot surgery:

- Get first and second opinions from qualified professionals. Talk to your MDA Care Center doctor and/or contact the American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society (800-235-4855) for a referral.

- Prepare yourself for a six- to nine-month process for a major foot reconstruction, including a hospital stay, casting, and physical therapy. You won’t be able to bear weight on the reconstructed foot for about six to eight weeks.

- Don’t plan to have both feet operated on at the same time unless you know you’re going to have a lot of reliable help at home.

- Don’t count on being free of orthoses after surgery. You may still require orthotics or AFOs.

Next Steps and Useful Resources

- A fashion blogger with CMT offers tips for looking and feeling your best.

- Find a CMT specialist at an MDA Care Center.

- Stay up-to-date on Quest content! Subscribe to Quest Magazine and Newsletter.

TAGS: Equipment and Assistive Devices, Featured Content, Healthcare, MDA Care Centers

TYPE: Blog Post

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.