Hope for the Future: A Family Living with Myofibrillar Myopathy Zaspopathy Raises Awareness for Rare Disease Research

By Rebecca Hume | Thursday, June 15, 2023

Janet Rodenhouse and her sisters have a lot in common. The seven women share a love for dancing, a deep appreciation of finding humor in all things, and a strong commitment to living life to its fullest. And five of them share a rare neuromuscular disease caused by a very specific genetic mutation.

Passed down through multiple generations, the family’s diagnosis of Myofibrillar Myopathy Zaspopathy is one of a group of myopathies resulting from mutations found in the muscle proteins. They are one of only two families in the world known to carry their specific inherited genetic mutation of the LDB3, a gene also referred to as Zasp.

Decades of study lead to diagnosis

Janet’s grandfather, George Mikel, and her father, Don Mikel.

Janet’s grandfather, George Mikel, and her great uncles, Mike and Claude Mikel, are the first documented cases of what would later become known as Zaspopathy myopathy. All three men exhibited weakness in their leg and arm muscles, difficulty climbing steps, and gait disturbances. In their 60s and 70s, progression ranged from walking with a walker or cane to eventually using a wheelchair for mobility. Their first clinical involvement was with Dr. Robert Griggs at the University of Rochester. Dr. Griggs studied the family disease through three generations.

Dr. Griggs wrote multiple articles in the 1970s as he investigated the cause of the men’s weakness and muscle deterioration. When their children, including Janet’s father, Don Mikel, began displaying symptoms in his mid-50s, along with a few of his adult cousins, Dr. Griggs began to study them as well. The research team at University of Rochester knew that the weakness was a result of a neuromuscular disease, eventually leading to an umbrella diagnosis of Myofibrillar Myopathy in the 1990s. After more than 30 years of clinical study, Dr. Griggs and his team discovered a specific genetic marker in 2005 that provided a clearer answer to the pattern of symptoms in the family.

Family genealogy and disease presentation

Characterized by initial weakness in the hands and lower legs, the first mild symptoms of Zaspopathy typically begin to present in the late 40s and early 50s of those carrying the mutation. A slow progression of foot and ankle weakness tends to lead to foot drop, ankle contractures, poor balance, muscle wasting, increased weakness, and the need to utilize mobility devices.

Janet recalls participating in studies with Dr. Griggs as a teenager, testing for weakness and other early markers. But it wasn’t until 2005 when Dr. Griggs and his team identified the LDB3 mutation that she and her family members were able to undergo genetic testing and confirm their diagnosis. The third-generation members carrying the gene included Janet, four of her sisters, and some of their cousins.

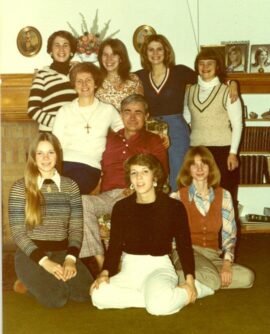

The Mikel Family.

Janet, now 67, began to recognize symptoms in her early 50s when she started to trip on uneven sidewalks and noticed difficulty lifting her toe and walking on her heels. Her sisters experienced similar symptoms, catching toes on uneven pavement and tripping easily. While the sisters’ symptoms are notably milder than their father and grandfather’s generation, the progression significantly impacts their daily lives and mobility.

“Now, as an adult in my late 60’s, I labor to walk and find climbing stairs especially difficult,” Janet says. “I carry a cane as a preventative measure for falls and to assist with uneven terrain and stairs. Standing for long periods of time challenges my ability to keep my balance and is quite exhausting. Standing erect and walking is practically impossible without shoes on. I even have a pair of shower shoes! Careful consideration is imperative when choosing footwear because it can make the difference in being able to walk. My greatest sadness with my progressive disability is the loss of my ability to dance. A sheer joy I took for granted but can no longer do.”

Growing up in a large community of people with disabilities and sharing the challenges of life with a disability, the sisters provide support and much needed laughter to each other.

“My father had a real dry sense of humor,” Janet says. “In difficult times, we can still find moments to laugh, because that is what heals us.”

The ZASP sisters

Janet and her sisters affectionately refer to themselves as the “ZASP Sisters”, sharing helpful hints with one another about the best shoes, exercises, walking sticks, and mobility tips. And of course, sharing lots of love and laughter. The two sisters who do not have the gene are still active members of the ZASP Sisters crew, sharing family support and investing time and energy into the sisters’ mission to find treatment for their disease.

The “ZASP Sisters” at NIH.

Over the last 40 years, Janet and her family have participated in clinical studies focusing on their particular form of muscular dystrophy. Janet and three of her sisters connected with the National Institute of Health (NIH) in 2018 and participated in a multitude of testing with the goal of furthering research and finding treatment for future generations.

“We went through various physical tests, muscle biopsies, brain MRIs, lung capacity testing… everything you could think of,” Janet says. “Our understanding is that the disease has been duplicated in mice and our hope is that this can advance the discovery of treatment.”

Unfortunately, the doctor initially overseeing this research is no longer with NIH and the sisters have not been able to access information regarding the current status of the study. But the sisters, who are also mothers themselves, remain motivated to raise awareness and support research efforts, especially for the sake of their children and grandchildren.

Hope for the next generations

Janet, who has five children of her own, is determined to make a difference for the future generations. While none of her adult children have chosen to undergo genetic testing, a few are now beginning to consider it. Of her sisters’ adult children, some have opted for testing while others have made the choice not to at this time. As an autosomal dominant disorder, affected individuals have a 50% chance of passing on the condition to their offspring. Among those who chose to be tested, four of Janet’s nieces carry the mutation.

John and Janet Rodenhouse with their five children.

“We are a very strong, very resilient, and incredibly loving family,” Janet says. “Any of our children, if they have it, then they will deal with it the best way that they can. But where we want to go now is figuring out how we can stop this. How can we make it different for their kids, and their kids?”

That goal is a key motivating factor in Janet’s dedication to raising awareness and funds for innovative research. She and her family have participated in a multitude of MDA fundraisers over the decades. This year, Janet and her husband are planning and executing an entire weekend fundraising event at her family’s winery in upstate New York.

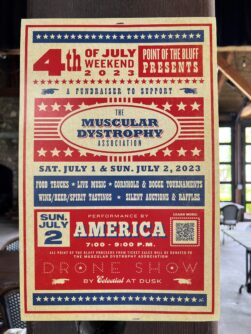

On July 1st and 2nd, the Rodenhouse’s vineyard, The Point of Bluff, is hosting an incredible weekend of fundraising, fun, and hope. Their venue includes two tasting rooms, bocce courts, outdoor picnic areas, and a hilltop concert pavilion that can accommodate over 1300 people. Proceeds from ticket sales, wine sales, and bocci and cornhole tournaments will be donated to MDA to support research for neuromuscular disease. In addition to live music in the tasting rooms, the band America will headline a concert at the large venue before the magical weekend commences with a spectacular live drone show, with over 400 drones creating images in the sky.

Event poster for the family’s fundraiser.

Janet is passionate about research advances not just for her family’s disease, but for all forms of neuromuscular disease. “We are late in the game,” she says, “There are so many families that get these diagnoses for their children when they are young. They need resources to adapt to their child living in this world with a disability. And they need research to find treatments to slow or stop the progression of these diseases. Our goal is more resources, more awareness, and more research.”

Next Steps and Useful Resources

- Learn more about the Fourth of July Weekend Fundraiser at The Point of Bluff Vineyards.

- Stay up-to-date on Quest content! Subscribe to Quest Magazine and Newsletter.

TAGS: Community, Fundraising, Genetic Testing, Relationships, Research

TYPE: Blog Post

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.