To Cath or Not to Cath?

By Margaret Wahl | Sunday, February 28, 2010

When ALS weakened Jane Cheng’s mother, her caregivers found it took a great deal of strength to help her transfer on and off the toilet.

“I twisted my ankle a few times when attempting to turn the pivot disk with my foot while supporting most of her weight,” says Cheng, who cares for her mother in central Pennsylvania.

The family eventually obtained a patient lift, which helped with transfers. However, says Cheng, “because of the time it took to complete a transfer, my mother sometimes felt like she didn’t have to urinate anymore by the time we got her on the toilet successfully.”

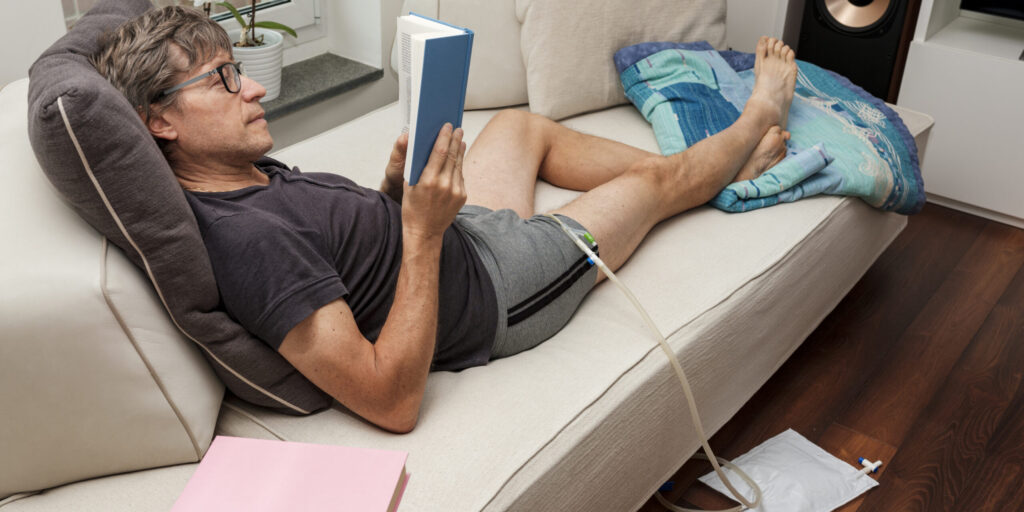

The eventual solution for Cheng’s mother, and for at least a few others with ALS, was to get a Foley catheter, which drains urine through a tube in the urethra that’s anchored in the bladder by a small, inflatable balloon. It’s also called an internal or “indwelling” catheter, or a “urethral” catheter. Urine drains continuously into an attached bag, which can be hooked to a chair, wheelchair, bed rail or leg (under clothes).

“The Foley helped reduce the number of times she had to get in the lift,” says Cheng, “and I think that being able to rest without worrying about getting up to use the restroom was a relief. Personally, I was relieved when the Foley was put in, because it decreased the risk for injury during transfers; helped my Mom conserve energy for other more important matters, such as spending time with friends and family; and helped caregivers conserve energy for more important matters, such as providing care for my mom.”

Cheng even speculates that “maybe my mom’s ALS wouldn’t have progressed as rapidly if she had not spent all her time and energy getting up and down from the toilet.” And, she says, “It’s sad to even try to think about the things we could have done together during that time, instead of struggling in the bathroom.”

The ‘pee problem’

Almost everyone with ALS faces difficulties with handling urination at some point. The problems are rarely with urination itself, but with handling the process in a dignified, quick and convenient manner, without jeopardizing health.

Medical professionals often balk at the insertion of any type of internal urinary catheter because of the fear of infection. But some people want them anyway and are willing to incur some risk for the other advantages.

In the initial phases of ALS, a urinal often is a good solution to the “pee problem.” These are easier for men than women to use, but there are some new styles that work for some women as well (see Resources section below). Urinals can be tucked into a large bag when away from home, as it’s generally easier to use one in a public restroom than to transfer on and off a toilet.

If urinals become unworkable as ALS progresses, the next step could be a mechanical patient lift to help facilitate toilet transfers, or an external urinary drainage device — again easier for men than women, although not out of the question for both sexes (see Resources section below). Other than skin irritation, leaks and detachments, there’s virtually no risk with an external catheter or urine collection device.

For women in particular, though, the external devices are tricky and may not provide the necessary coverage, comfort or convenience.

Foley catheters: the downside

Medical professionals generally frown on Foley catheters and other internal catheters for ALS patients. ALS, they say, usually doesn’t affect urinary functions specifically, even though in general, muscle weakness can make it very difficult to get to a bathroom, use a toilet or sometimes even use a urinal or bedpan. (Some people with ALS also experience urinary urgency.)

Their main objection to an indwelling catheter is the danger of infection this type of device poses.

“It’s easy for a Foley catheter to become contaminated by bacteria,” says nurse Lora Clawson, director of ALS Clinical Services at the MDA/ALS Center at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “The anatomical structure of where the urethra is in relation to the rectum leads to cross-contamination, even with normal female hygiene, let alone a catheter.”

Antibiotics can be used to successfully treat urinary tract infections, but, Clawson cautions, they’re not without their own risks. “Anytime you’re exposed to an antibiotic, you can develop antibiotic resistance,” she says. “After a time, there are constant resistant bacteria present. Antibiotics also can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, skin rashes and yeast infections.”

She prefers that ALS patients try other solutions before opting for an indwelling catheter. “There are some new designs of female urinals that I encourage patients to try,” Clawson says. “The mouth of the urinal has to be form-fitting to a woman’s body.”

Some women, she says, have come up with “creative solutions,” such as wearing a dress without underwear, sliding down to the edge of the wheelchair and then peeing in a cup or other container.

For men, she says, anatomy makes the urinary challenges much easier. Many men with ALS can use a traditional urinal without much trouble. They also have the option of an external catheter, which fits over the penis and connects to a tube (see illustration, right). It doesn’t carry any of the infection-related complications of the indwelling catheter, although it can cause skin irritation.

Gabriela Harrington-Moroney, a nurse at the Eleanor and Lou Gehrig MDA/ALS Center at Columbia University Medical Center in New York, is also unenthusiastic about indwelling catheters because of concerns about infection and the difficulty of getting patients the nursing care that these devices require.

Having an internal catheter of any type, she notes, “requires nursing intervention. A nurse has to go out every four weeks or so to change the catheter, so you have to have an ongoing visiting nurse service in place, and sometimes insurance doesn’t want to cover it.” (She recommends that any catheter be changed every four to six weeks and that a nurse regularly look for signs of infection or other problems.)

On the other hand, she concedes that there are problems for people who need assistance to get to the toilet or use a urinal as well. “We’ve had some patients with urinary tract infections because their home health care worker may go home at 8 p.m., and they don’t urinate all night because they can’t get up on their own.”

And then, there are those quality-of-life issues, which go beyond the medical issues and can be hard to assess.

“We talk a lot as nurses and physicians about quality of life for patients,” says Harrington-Moroney. “Yes, maybe there are downsides and pitfalls to catheters, but with patients with ALS, what quality of life do they want to have? Some of them won’t go to dinner because they can’t get to a bathroom fast enough and don’t want to wear a diaper. Maybe we should look at that more closely.”

Loves her Foley

Karin Kallweit of Toronto, a former nurse, was only 31 when she first noticed weakness and muscle wasting in her right hand that would later prove to be ALS. Now, as she approaches her 42nd birthday, she has almost no movement from her shoulders down but manages to live in her own apartment with only part-time assistance.

When she was still able to use a walker, she found she couldn’t unbutton her pants in time in the bathroom. Now, she can no longer transfer to the toilet at all.

“I used pads for a little bit,” she says, “but since I’d rather not have anybody during the day, one of the problems was that you need to get them changed regularly. I used to be in nursing, so I knew people who had catheters. I thought, you can always take it out if you don’t like it.” (Note: This may not be possible in all cases, because of bladder changes over time caused by the continuous drainage of urine.)

Her request was not initially greeted with enthusiasm. “I went to the ALS clinic and asked the nurse about it, and she acted like it was the most horrible thing,” Kallweit recalls. “She said, ‘You’re going to get bladder infections.’ She made me go to the urologist at the hospital, probably thinking he would talk me out of it. But I talked to him, and he said, ‘Sure,’ and put one in right in the office.”

That was eight years ago. Kallweit has had two bladder infections (each after a bowel accident) and some difficulties with clogging of the catheter, but she’s never regretted her decision.

“I don’t need anybody during the day to change diapers,” she says. “I go out whenever I want, because I don’t worry about smelling like pee or sitting in a wet diaper. I’m up in my chair all day. I’m in downtown Toronto, so there’s always something going on. If I go out with my girlfriends and I want to have three or four cups of coffee, I don’t worry about it.”

Kallweit admits the Foley isn’t for everyone and does have potential complications. “If you don’t drink enough, or if the catheter has a little defect, the little hole at the end of the part that is in the bladder can become plugged up. It happens every four to five months.”

To help prevent infections and clogging, Kallweit drinks plenty of fluids and takes cranberry pills. She also takes a drug called Ditropan, to counteract bladder spasms.

“If you’re someone who doesn’t like drinking, then the catheter is probably out for you, because you’ll get more infections if you don’t drink enough,” she says.

For herself, she says, “I wouldn’t live without it.”

Suprapubic catheters

Foley catheters aren’t the only game in town when it comes to internal urinary drainage.

A suprapubic catheter, instead of being inserted through the urethra, is inserted into the bladder through the abdomen, in a surgical procedure requiring anesthesia. As with Foley catheters, suprapubic catheters can cause infections. But they have their fans too.

Freedom and comfort

“Walk a mile in my shoes and you’d understand,” says Sandra Scott about her choice of a suprapubic (above the pubic area) catheter. Scott, 60, has ALS and lives in Portage La Prairie in Manitoba, Canada.

Like Kallweit, Scott values her independence and doesn’t like the idea of having to transfer to the toilet every few hours (for which she needs the help of a patient lift) or having to wear diapers. In short, she says, she didn’t like having to have her life “planned around urine.”

Scott at one time considered getting a Foley catheter, but she rejected the idea.

“I had experienced them before and didn’t appreciate the feeling of a tube ‘there’ and how it felt being inserted and taken out,” she says. “Also, I’m a married woman with a normal, albeit changed, sex life.”

She asked her pulmonary specialist for a referral to a urologist and did some Internet research on catheters “not only for medical facts but for people with them. I could still speak and had no problem being my own advocate,” Scott says.

Her suprapubic catheter was inserted above the pubic bone during outpatient surgery. The area around the insertion site (“stoma”) is cleaned twice a day, and the tube is changed every four weeks by a home health care nurse. The bag is changed weekly. “It’s simple to care for,” Scott says.

Scott says she has a better quality of life with her suprapubic catheter than she had without it, because it’s clean and odor-free, she doesn’t have to wear diapers or worry about being away from her lift, and she no longer has rashes or a “sore, burning bottom” from sitting on pads in a chair.

She and her husband sleep better without “having to wake up at least twice and usually more to go through the rigmarole of putting me on and off the bedpan.”

Scott says she can “wear proper clothes and underwear” and drink as much as she wants without worrying about additional trips to the bathroom.

“Increased liquid will decrease the possibility of bladder and lung infections and skin breakdown and aid bowel function,” she says. “Generally, it’s a lot easier to manage than ‘regular’ voiding.”

Scott says there have been “no embarrassing accidents” and “more freedom and comfort overall” with the suprapubic approach.

Making the decision

Consideration of an internal catheter requires a discussion with your doctor and almost certainly a referral to a urologist.

The urologist will likely assess:

- your general state of health;

- your ability to care for the catheter, including having a professional change it regularly;

- your willingness to drink plenty of fluids (or take fluids via a feeding tube) and take other recommended infection-preventing measures;

- the accessibility of medical care if complications should arise; and

- your ability to withstand anesthesia (suprapubic catheter only).

Unlike other medical interventions in ALS, such as a tracheostomy or feeding tube, there are no clear medical benefits to internal catheters and in fact, there may be medical downsides, such as the risk of infection. The main benefit, say those with internal catheters, is improved quality of life for themselves and their caregivers. These folks often take a very pragmatic view.

As one man with ALS said of his suprapubic catheter, “What’s another hole in this body, anyway?”

Resources

At Home Medical

Suwanee, Ga.

(770) 476-0490

(800) 526-5895

www.athomemedical.com

External urine collection systems for men, external collection system for women (Convatec Female Urinary Pouch)

BioDerm

Largo, Fla.

(727) 507-7655

(800) 373-7006

www.bioderm.us

Unique Liberty external collection system for men (video on Web site)

West Marine

Watsonville, Calif.

(800) 262-8464

www.westmarine.com

Little John portable urinal for men with Lady Jane adapter for women

Next Steps and Useful Resources

- MDA’s Resource Center provides support, guidance, and resources for patients and families, including information about ALS, open clinical trials, and other services. Contact the MDA Resource Center at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 or ResourceCenter@mdausa.org

- Stay up-to-date on Quest content! Subscribe to Quest Magazine and Newsletter.

TAGS: Caregiving, Healthcare, Resources

TYPE: Blog Post

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.