Recognizing and Treating CMT in Kids

By Elizabeth Millard | Friday, September 10, 2021

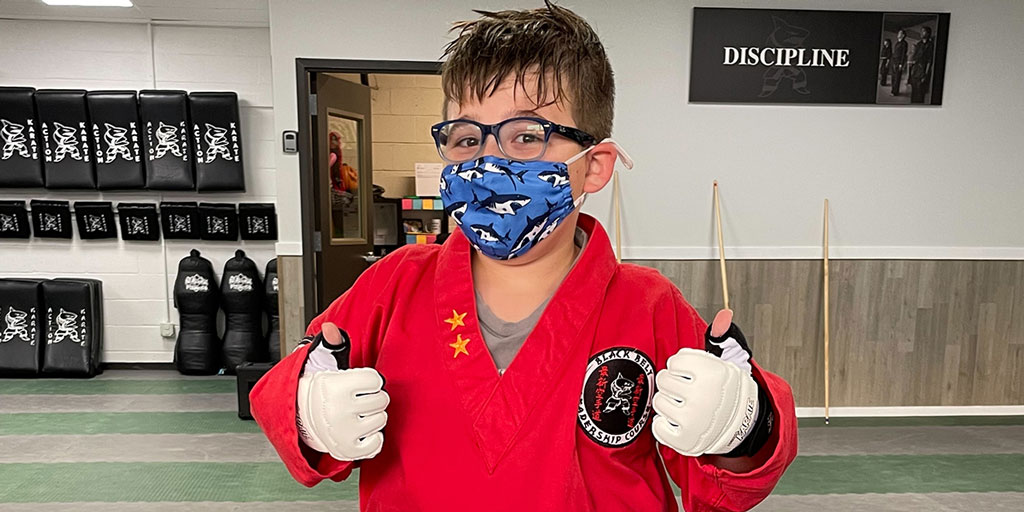

Like many middle-school kids, 11-year-old Callen, of Emmaus, Pennsylvania, has turned his mom, Jamie Moulthrop, into a chauffeur, she jokes. He participates in karate, baseball, hockey, and surfing, and he meets up often with friends at the pool and splashes around for hours.

Unlike the other kids around him, though, Callen has Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT), a progressive neuromuscular condition that significantly impacts muscle development and nerve firing. Making sure he stays active isn’t just good for his social connections, it also plays an integral part in slowing the loss of muscle mass and preserving his mobility for as long as possible.

Callen’s care team helps him find adaptations to participate in sports, including wearing leg braces for stability.

“He isn’t gaining muscle, but we focus on making sure he doesn’t regress,” Jamie says. “Some sports need to be adapted and there are things he can’t do, like use the diving board or go on slides, but the kids around him adjust for that and they find other ways to play.”

Symptoms and diagnosis

There are many different types of CMT, and age of onset varies from birth to adulthood depending on the type. CMT in children often begins as discomfort, weakness, and numbness, usually in the legs and feet, according to neurologist Ava Yun Lin, MD, who runs the pediatric CMT clinic at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital at University of Michigan. The disease is rare and its progression often is slow. As a result, it can take years for families to get a diagnosis and find the right specialty care.

For example, Callen first started showing signs when he was 18 months old — like falling often and struggling with mobility — but he wasn’t diagnosed until age 5. By then, he’d seen numerous doctors, Jamie says.

The symptoms can be subtle. Kids may get fatigued quickly because it’s harder for their nerves to communicate with their muscles, Dr. Lin says. They may sprain their ankles often or complain about sore feet because of contractures in the Achilles tendon. Some parents notice their kids seem to always lag behind others at the playground or, if the condition affects the hands, children may frequently drop objects like toys, markers, or silverware.

Diagnosis involves doing nerve testing as well as genetic testing. There are more than 100 genes that may be affected, and the combination of those two tests helps pinpoint which type of CMT may be involved. For the most common type of CMT, children are usually diagnosed between ages 6 to 10. However, the condition can be detected earlier if symptoms are notable enough to lead parents to ask for a neurologist referral.

For example, Pennsylvania resident Becky Clark suspected something was happening with her son, Nick, when he began walking awkwardly on his left foot at age 3. He also was falling often, so she took him to orthopedists, who suggested he’d grow out of it. A pediatrician prescribed physical therapy (PT), but it wasn’t helping. Finally, the physical therapist sent them to a neurologist.

“The moment they saw him walk in the door, they suspected it was CMT, and it was a relief to get a diagnosis because it meant we could finally pursue treatment that was appropriate,” she says.

Treatment options

Knowing which genes are involved in a particular case of CMT may not determine therapy now, but Dr. Lin says that’s likely to change, maybe soon.

“Gene identification is very important because there are gene-based therapies we expect to be rolling out, possibly within a few years, since clinical trials are already in progress,” she notes.

In the meantime, the main treatment for any type of CMT is PT and occupational therapy (OT) to protect the nerves from additional injury and preserve function and mobility. These therapies also help reduce contractures, which happen when muscles, tendons, or joints start to shorten, potentially causing pain and mobility issues.

“The emphasis for any type of CMT in children is prevention, prevention, prevention,” Dr. Lin says. “Not only does that help slow the progression, but more importantly, it reduces injury risk.”

Physical and occupational therapists can be involved in CMT care right from the beginning, including helping with diagnosis, educating the whole family, and suggesting modifications for sports or everyday activities, according to Allison Fell, an occupational therapist at Connecticut Children’s, which is a CMT Center of Excellence.

“We look at what they need and want to do, from getting dressed to playing football,” she says. “We also work on proper grasp of objects, fatigue, sleep, and numerous other aspects of CMT.”

Balance also is a big part of PT, adds Adam Brown, a physical therapist at Connecticut Children’s. That might mean working on going up and down stairs or learning to stabilize the ankles without bracing. Because children are still growing, physical and occupational therapists often need to adjust for their development, which might require more frequent therapy sessions than adults with CMT.

Treatment often involves following a program at home, such as doing stretching exercises and wearing braces during certain activities or at night. In addition to wearing braces, the strategy that’s helped Callen and Nick the most is to simply keep moving as much as they can.

“Sometimes, the CMT is still frustrating for Nick because he’s not as fast as the other kids,” Becky says. “But he has such a good attitude about it, and the therapy is helping him improve his coordination. He’s like any kid — he just wants to get out and have fun.”

For help finding a neuromuscular disease specialist or MDA Care Center, contact MDA’s National Resource Center at 833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321) or ResourceCenter@mdausa.org.

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.