Stem Cell Innovations Drive Advances in Muscle Regeneration

By Andrew Zaleski | Friday, February 28, 2025

5 Second Summary

A new frontier of medicine looks into how to regenerate muscles lost to neuromuscular diseases using advances in stem cell research.

A group of scientists and patient advocacy organizations met in July 2024 to discuss one of the biggest questions in the world of neuromuscular disease: Can muscle be restored after it is lost to a muscle disease?

It was MDA’s inaugural Muscle Regeneration Summit, a first-of-its-kind effort not only to summarize the research to date on regenerating muscle but also to outline strategies currently underway to improve the lives of people struggling with muscle disorders.

It’s not difficult to understand what the ability to regenerate muscle tissue would mean for people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD), myotonic dystrophy (DM), and many other conditions that cause muscles to weaken and waste. Everyday tasks would become easier. Overall health, perhaps even greater longevity, might follow. The neuromuscular research community has been discussing the possibility of bringing back deteriorated muscle — but lacking real-world methods to do so — for decades.

“We have been working on this problem for many years now, but it’s clear that there are still things that we don’t understand about muscle regeneration,” says Sharon Hesterlee, PhD, MDA’s Chief Research Officer.

Yet this summer’s Muscle Regeneration Summit ended on a promising note: We’re closer than ever to discerning and deploying the science of muscle regeneration. Much of this optimism has to do with understanding the function of stem cells.

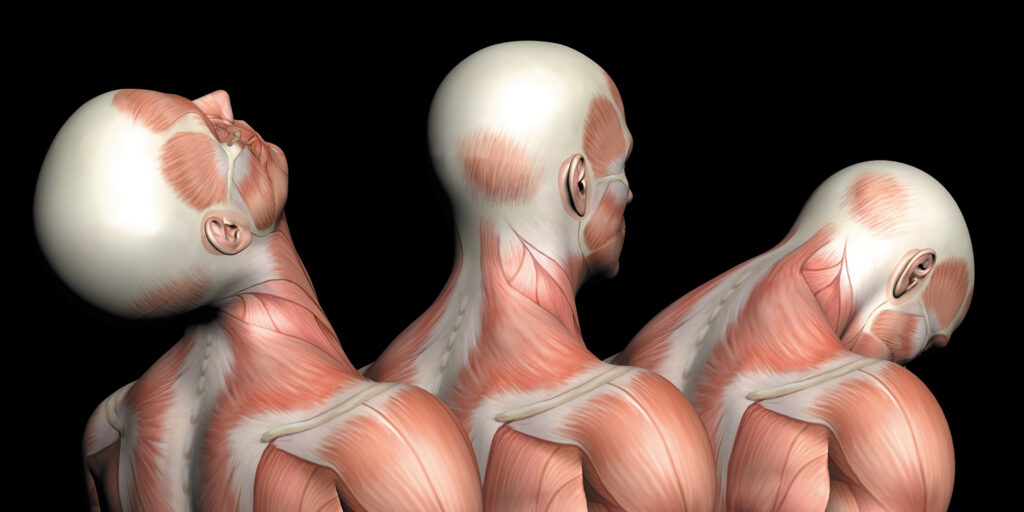

Stem cells and muscle

Stem cells help the human body manufacture new muscle tissue. Whenever you perform a strenuous activity, whether it’s lifting weights at the gym, taking a brisk walk, or doing yard work, microtears form in the muscles. At this point, a specific type of muscle stem cell rushes in to make repairs.

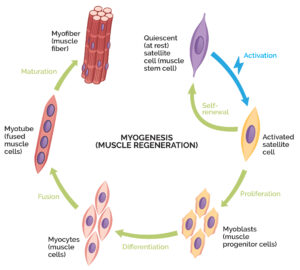

Stem cells are basically primitive cells that can differentiate into more mature cell types. Muscle stem cells are known as satellite cells, and when muscles become damaged, satellite cells wake up and begin replicating. Some of these cells stay behind to make sure the population of satellite cells remains. Meanwhile, the other satellite cells begin to take on features of muscle cells and fuse with the targeted muscle fibers to repair and rebuild it, a process known as myogenesis.

In neuromuscular diseases, this process may be thrown off. For example, in some cases of muscular dystrophy, stem cell function is altered, causing myogenesis to be less efficient. In addition, the muscles are more prone to injury, putting more burden on the satellite cells and potentially exhausting the body’s capacity to repair muscle.

The potential of stem cells

Myogenesis is a process where muscle stem cells repair and rebuild damaged muscle.

Researchers are now looking at ways to use stem cells to drive muscle regeneration. Enhancing the body’s natural ability to build muscle through myogenesis is one option. By stimulating the satellite cells inside the body, the thinking is that enough muscle could be replaced to keep up with ongoing muscle deterioration.

However, a genetic muscle disease poses a problem. “If you are asking a patient with an underlying genetic mutation to generate more muscle, keep in mind that the newly regenerated muscle also harbors the genetic defect,” says Angela Lek, PhD, Vice President of Research at MDA. In other words, the body is regenerating muscle, but not healthy muscle.

Combining muscle regeneration with gene therapy could effectively solve this problem. Imagine someone with myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1), which is caused by a faulty DMPK gene. Snipping out or blocking the mutated gene in muscle cells could theoretically allow the satellite cells to regenerate muscle that doesn’t carry the defect.

There are currently only two gene therapies approved for neuromuscular diseases: Elevidys for DMD and Zolgensma for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). However, many more are in preclinical studies or clinical trials to treat diseases such as limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD), X-linked myotubular myopathy (MM), and Pompe disease.

The other option discussed at the MDA summit involves transplanting muscle cells that do not harbor disease-causing mutations. In 2012, two researchers were awarded a Nobel Prize for their work on reprogramming mature cells to a more primitive state, called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). This was a significant breakthrough because it meant that any cell could be extracted from the body and treated in a lab to make it an iPSC. The iPSC could then be differentiated with growth factors to create any mature human cell type. Imagine taking a skin cell from a patient with DMD and creating a healthy muscle cell by correcting the mutation in the dystrophin gene, then transplanting it back into the body to help regenerate lost muscle.

Challenges remain with this approach, too. Getting the new muscle cell to engraft (grow and make new cells in the body) and properly function is a hurdle. Dr. Hesterlee points out that muscle degeneration leads to inflammation in the body, which may disrupt a healthy cell’s ability to settle in and try to repair damage. Dr. Lek adds that engrafted cells may not contribute to regeneration the same way naturally occurring stem cells in the body do.

“It’s the holy grail to transplant into patients healthy stem cells that can regenerate new muscle and also maintain a regenerative pool of muscle stem cells,” Dr. Lek says. “Everybody knows what the end goal is; we just don’t know how to get there yet.”

Signs of progress

Researcher Rita Perlingeiro, PhD, works with muscle stem cells.

Despite the obstacles, there’s great cause for hope on the horizon. Rita Perlingeiro, PhD, is a faculty member at the University of Minnesota Department of Medicine with two decades of research experience in generating muscle progenitor cells from iPSCs. She is also the lead inventor of the MyoPAXon platform for muscle regeneration, licensed by Myogenica, a company she cofounded in 2022. The platform is based on iPSCs that express Pax7, a transcription factor that develops iPSCs into myogenic satellite cells. Animal studies demonstrated that transplanted MyoPAXon cells produced healthy muscle fibers, generated new muscle stem cells, and expressed dystrophin, a protein in skeletal muscle that is lacking in DMD.

A first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial, led by Peter Kang, MD, at the University of Minnesota, is recruiting participants with DMD who are non-ambulatory (not able to walk). This year, the trial will start testing the MyoPAXon platform on a muscle in the upper foot. If it demonstrates MyoPAXon’s safety, the team may move on to tests in other muscles, like those in the hand.

“Of course, as scientists, we really want to target all the muscles,” Dr. Perlingeiro says. “But to make progress, we have to think incrementally and move step by step.”

Keeping the conversation going

MDA is committed to helping researchers further demystify the biological processes behind rebuilding healthy muscle tissue with neuromuscular diseases. As part of this effort, MDA is inviting researchers to submit grant applications for projects that study muscle regeneration. In addition, MDA is fostering more discussions among the world’s foremost neuromuscular researchers, with muscle and nerve regeneration on the agenda during the 2025 MDA Clinical & Scientific Conference.

Dr. Hesterlee and Dr. Lek feel confident that it will not be decades before advancements in stem cell therapies lead to new therapies — ones that empower people with neuromuscular diseases to live longer, more independent lives. It’s also apparent that the expanding scientific knowledge around muscle regeneration has

broad applicability.

“Most of these muscle replacement strategies could be used in any muscle disease,” Dr. Hesterlee says. “If we can figure out how to do this in one muscle disease, we can probably do it in many others.”

Andrew Zaleski is a journalist who lives near Washington, DC. He wrote about living with myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) for GQ magazine.

Next Steps and Useful Resources

- Did you know that MDA has been driving groundbreaking neuromuscular research for 75 years? Here’s a timeline of our major milestones.

- Learn how researchers are working to translate research advances across neuromuscular diseases, even those considered ultra-rare.

- Stay up to date on Quest content! Subscribe to Quest Magazine and Newsletter.

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.